The Liberum’s science fiction author and specialist, Emad Aysha, interviewed by Haarf magazine, 28th edition. Haarf is a particular section of the mother newspaper, Al-Dustour (meaning the constitution). It is an honour for our in-house specialist to be featured by in one of Egypt’s leading literary magazines.

By Hanan Uqayl

Could you tell us more about your background and science fiction work?

“I’m a social scientist and university professor (part-time) who initially taught and wrote mainly in English. My parents are Arabs, but I was born in the UK in 1974 and grew up in the British educational system.

I received my PhD in England in 2001, in International Studies, and have been teaching at English-language universities in Egypt since then till 2015, when the academic market dried up. I publish and translate many journalistic works, but unfortunately, those markets also dried. In 2015, I finally decided to try my hand at my great love, which is science fiction.

Sadly, I haven’t produced much because I joined the Egyptian Society for Science Fiction (ESSF) in 2016 and got into writing ‘about’ science fiction more than actual stories. Still, I have one anthology in my name – The Digital Hydra. I got my friends to translate my stories for me. I have a planned novel in draft form, set on Mars, and a spy series set in the future with some unlikely Arab heroes.”

You participated in editing the book ‘Arab and Muslim Science Fiction’. Tell us a bit more about the features of Arab science fiction literature. Is there a gap between Arab and Western novels in science fiction?

“Let’s start with some statistics about the book and just how ‘amazing’ it is 29 countries represented with 45 contributors (14 women) from 4 continents, with 45 chapters - with detailed academic-length articles (13), and easy-going interviews (17) and personal essays (15). I coedited the book, wrote two chapters, and wrote all the translations.

There’s no book like it on the market, before or after. There are other books about Arab SF but by foreign academics and not told from the first-person perspective of our writers, editors, critics, publishers and bloggers. People talk about their personal experiences and the uphill battles they’ve fought, what is unique about SF in their country, and what’s wrong with SF, which is different from other countries. You’d be shocked to know what happens in Libya, Yemen, Afghanistan, and Uzbekistan.

The most prominent feature revealed in the book is that… as authors in the Arab world, we all live on little islands by ourselves. We don’t know what’s happening in the country next door or even read what previous generations wrote in the same region. We start from scratch, which wastes time and forces us to imitate the more established SF, the West.

But we do have some advantages. We have our way of telling stories and presenting the hero’s journey. We have Al-Shatir Hassan, Al-Sira Al-Hilaliya, and The 1001 Nights, and some of our more original authors draw from them to write exciting and different novels. These include Ahmed Salah al-Mahdi, Dr. Hosam Elzembely (the founder and director of the ESSF), and Dr. Faycel Lahmeur in Algeria.

As for the ‘gap’, I’d say quite big. We don’t write across the full range of subgenres. We have First Contact and Alien Invasion, steampunk and cyberpunk and dystopia, and distinctive qualities regarding some of these subgenres. However, we still haven’t done Solarpunk and Hopepunk, and we’ve only got a handful of authors and novels in any of these more minor fields. We don’t have social science SF, like Frank Herbert in Dune or Isaac Asimov in Foundation, although I’ve some short stories focusing on that.

We are developing our own genres. There’s Sufi science fiction, which was there in Dr Mustafa Mahmoud in the 1960s and now in Dr Faycel Lahmeur and some less well-known Egyptian authors. We have conspiracy theories in SF, like Dr. Taleb Omran in Syria and Eslam Samir Abdel Rahim in Egypt (Alexandria).

Moataz Hassanien has his kind of dystopia novels and stories. We have inventive and colourful Space operas and parallel dimension stories and novels by Dr Abeer Abel Galil Ibrahim, Ammar A-Masry, Wael and Mahmoud Abdel Rahim, Mahmoud Fikry and Sandra Serag. We like expanded universes of exciting cultures, people and planets and constantly want to learn from other civilisations.”

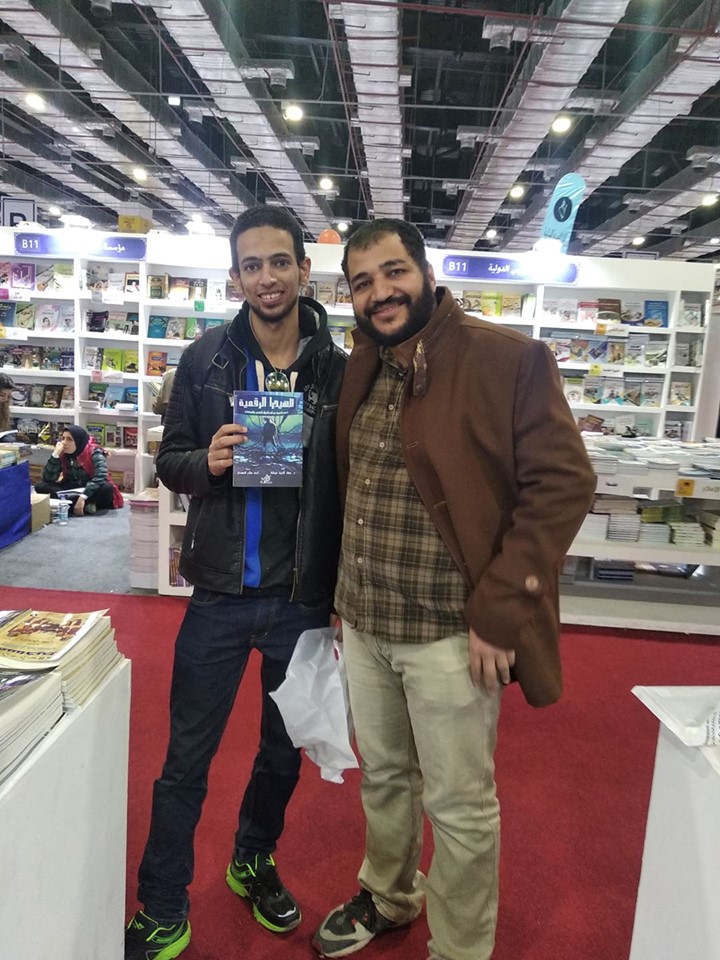

PARTNERS IN CRIME: Friends and fellow SFF authors Ammar Al-Masry and Ahmed Salah Al-Mahdi, at the Cairo International Book Fair, holding a belated copy of my Digital Hydra anthology.

From your follow-up of Arab science fiction novels, what are your main concerns?

“Arabs and Muslims are very moral people, and more so are Egyptians! We want the good guys to win, be merciful to the enemy, and win him over to our side. We want everybody to live in peace and harmony. I’ve seen this in Space Operas and alien invasion epics. We also don’t like wars and often try to imagine ways to live in peace with alien civilisations and mix with them. We don’t have this Darwinian way of thinking. We’re so nice!

We think of novels and stories as moral and scientific instruction to people, especially young readers, teaching lessons on how to be modern, democratic, and a democratic leader, to take people’s opinions, and to have votes, even in an emergency. So that's good, too.

Generally, we’re more concerned with the family unit than Western authors. We’re more concerned with spiritual values and don’t like a materialist reading of history or what drives people, which counts as success or failure. We’re more concerned with the environment and want to turn the deserts green.

In a civil war, people turn against each other and do not trust each other. Moral breakdown. That’s what dystopia means to us. Read the first chapter of Otared, and you have a story of a businessman who lost all his money and murdered and ‘ate’ his family. You know this is coming from the headlines, the stockbroker who butchered his family after he lost all his money on the boursa. Then, he died later in prison. Also, you have The Queue by Basma Abdel Aziz, which is all about bureaucracy and bread queues and people fighting over breadcrumbs and trying to steal each other’s inheritance. It is an old story but told in a new, funny, and technological way.

The ESSF did a unique anthology on economics, the first in the Arab world. Nobody has ever done a group of stories about economics – free trade theory and competition and monopolism and economic dependency on one commodity (like oil) and multinational corporations trying to steal our wealth and inventions; and if money has any meaning if it's virtual and if money is essential if you can be close to your loved ones (must meet them virtually). It’s great and even unique compared to Western SF. “

Criticism of science fiction literature in the Arab world is still limited; why is that?

“Yes, it’s minimal. I will explain why. I read it indirectly in a book by Dr. Gaber Asfour. He revealed that in the Nasserist era, I think in the 1960s, a decision was made to prioritise socialism, realism and Marxist materialism over everything else, specifically the imagination. Satire suffered, surrealism suffered, and even Sufism suffered!

I’d also say the critics don’t know what science fiction is. They think it's surrealistic and a waste of time. They don’t understand that SF is a practical and realistic genre of literature. It’s about dreaming of a better future, a feasible future you can make through hard work, intelligence and determination. A combination of technology and policy. Oh, and morality!

But things are changing. There are many more programmes on Nile TV about science fiction than ever, with interviews of young authors, and the Writers’ Union has a sci-fi section now and has held several conferences on SF and related topics.”

This is a truncated version of my original interview on 22 July 2024, in English. Other notable names in the 28th edition of Haarf include Dr Hosam Elzembely, El-Sayyed Negm, Salah Maati and Ian Campbell.