I just visited China to participate in the Chengdu World Science Fiction Convention and the Hugo Awards (18-22 October). During my 9-hour flight from Cairo, I read Yasser Bahjat’s alternative history novel Yaqteenya: The Old World (2015). I finished this page-turner novel in a record 6 hours.

By Emad Aysha

Sure, there are some flaws here and there, with some plot threads and character arcs not pursued, but overall, it is a formidable piece of work on the what-could-have-been front. Not to mention a very distinctive Arabic and Islamic contribution to SSF.

A yaqteenya is a pumpkin, the name the alternate history residents of a Muslim Mesoamerica give their continent. A band of brave and desperate Andalusian Muslims escaped extermination at the hands of the conquering Spaniards, almost starved to death after reaching the shores of the New World.

It was saved by the fruit's flesh, just like the Prophet Jonah. Only an Arab would think up such a poetical name. And this from an engineer and TEDxer.

In this world, the Spaniards, thank heavens, haven’t discovered the new world, and the Ottomans have conquered Rome. Sadly, and strangely, Spain is still Spain, a Catholic autocracy bent on stamping out anything diverse or different in terms of culture and religion.

To make matters weirder, the Muslim nations that now populate the new world don’t know they aren’t the only Muslims left. They date their history to the fall of Grenada and have a self-imposed isolation policy to protect yaqteenya from being discovered by the evil old Spanish crusaders.

Alas, they can never isolate themselves from history, the ugly hand of fate where Arabs become arrogant and divided and begin to pray on each other and allow their enemies to gang up on them. That is what has happened to their beloved yaqteenya, being torn apart by civil war despite all the tolerance and advancement of science – they invent the camera and gramophone in this alternate world.

The nominal narrator of the story is an Athenian who escapes to the old world to prove to the rebels that the ancient world does exist and is not a fiction invented by the Moors (the settler Arabs) to control the natives.

The hero, not coincidentally, is half Moor, half native, taking the best of what al-Andalusia had to give humanity – tolerance and culture hybridisation – writ large for the benefit of the modern literary audience. At the same time, the story is also a cautionary tale about science and technology. They are just tools and can be used for good or for evil.

You notice this in the geographic portrayal of the yaqteenian civil war. An upstart, a native who is nonetheless Muslim and Arab-speaking, wants to kick out all the so-called Moors and make his bid for power, and wouldn’t you know it, he resides in the Western part of the continent. He is privy to steam technology and the more advanced gunpowder weapons. The yaqteenians have a card up their sleeve, combining their spiritual heritage as Muslim with the nature-loving natives, allowing certain gifted people (like the hero) to commune with the animals and even rocks and mountains and command them to help in the fight. It all depends on their totems- how they are given their adult names- with spiritual training by a grandmaster.

Explicit references are then made to the Prophet Solomon (PBUH) and mantiq al-tayr, the speaking or conversation of the birds, both in Quranic exegesis and in Sufi literature.

An indicator of this is when the hero is on scout duty against an enemy position and uses a hawk he can converse with – he saved it when it was a chickling – one of the bad guys shoots at it with a telescopic lens.

The good guys almost win the day, but tragically, the rebel leader has mastered some of these skills too and uses them at a decisive point in the battle to turn the tide in his favour. So, the ultimate lesson is to tame the ego since the science of spiritual things is just another tool for dominion no different than quantum physics. (I become death, the destroyer of worlds, the Hindu quip from old Oppenheimer, if you remember).

I loved this thematic and plot setup for a whole other reason. It dovetailed, if you pardon the expression, with my own stories. I’d written a Martian epic, published in summary form as “Lambs of the Desert”, where I have a Bedouin boy proudly proclaiming that the Arabs will win the war against the Yankee imperialists on the red planet because they fight for Mother Nature.

So Mother Nature will fight for them. I don’t do anything mystical, sadly, in retrospect. Still, I have clever usage of brainwave analysis, genomics and radio communications to get the transplanted wildlife on the side of the Arab settlers. That most definitely includes camels, by the way.

Yasser Bahjat bends and blends genre boundaries as only an Arab would do. I’m too much the complex SF and social science SF type of guy. Genre boundaries must be questioned constantly because what we think we know – science vs. superstition – needs to be examined, too.

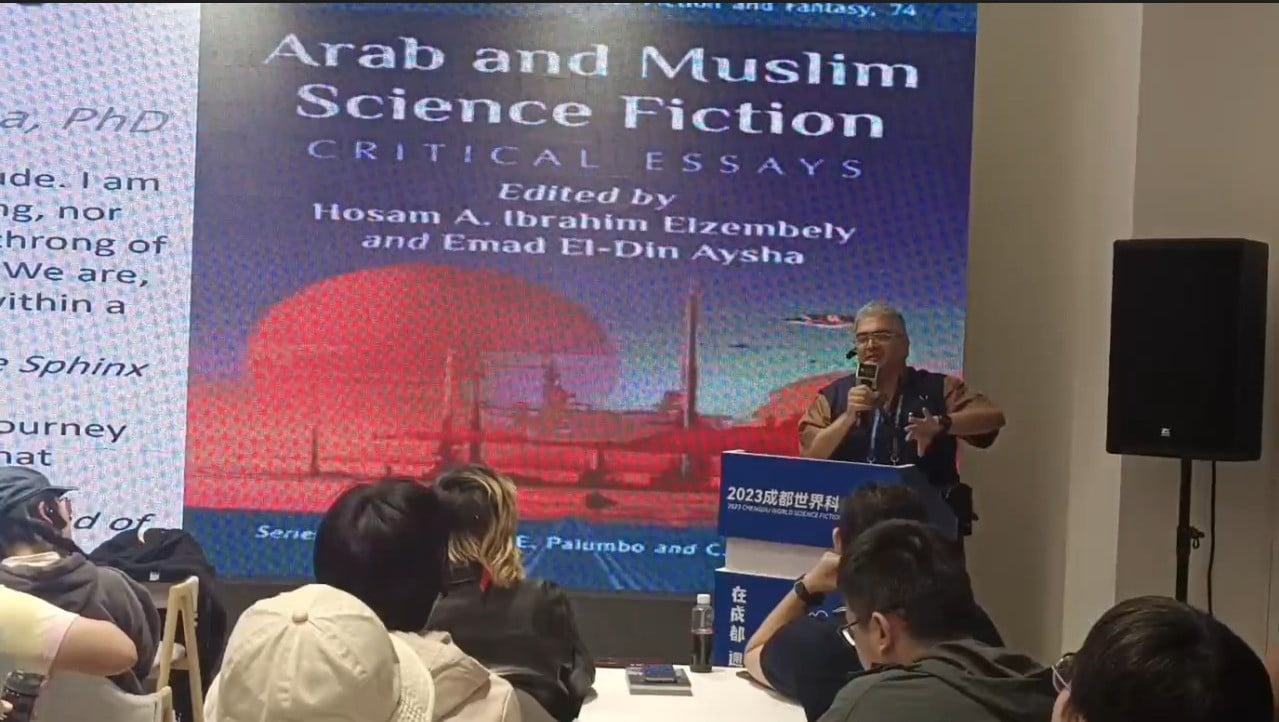

GRAND SLAM: One of the highlights of the Hugo Awards was the prize for best fanzine going to 'Zero Gravity News'. Here's me with its progenitor, RiverFlow, someone we had the foresight to interview here at The Liberum a goodly while ago. Thank him for the photo too. My smartphone camera was terrible!

Something I pointed out in my keynote speech at the WorldCon’s Afrofuturism workshop (22nd October) is to ask if matter is truly inert as Aristotle says, or is being forced, as African cosmology teaches us. SF has to anticipate such questions and explore good and bad outcomes. And so science fiction helps us re-conceptualize ourselves and our place in the grander scheme of things.

All the more reason for science fiction from the Global South and the Far East incidentally, bringing fresh and different world-views to the tableau of mainstream, Anglo-dominant SFF. To quote Wole Talabi from the Afrofuturism workshop, nobody else can say what they think or be encouraged to think for themselves if one person is shouting in a room. That’s what mainstream SF has done, inadvertently, as much as he and I both like Western sci-fi. Without cultural interactions with the rest of us, SF will stagnate. And if we isolate ourselves, we’ll stagnate too. Just look what happened to the not-so-poor yaqteenians!