Ever since Grotius argued that war could be governed by reason, the project of “civilising violence” has haunted the legal imagination. From the Hague Conventions to the Geneva Conventions (1899-1949) and their additional protocols, legal efforts have aimed to rationalise the chaos of conflict, to impose order through detailed regulations. Yet in modern war, public outrage tends to rise in proportion to the body count, as though some tacit algorithm determines the moment a conflict becomes morally intolerable.

By Rafael Baroch

Terms such as “proportionality” and “civilian protection” under international humanitarian law (IHL), and “right to self-defence” under the UN Charter are invoked to legitimise actions and mitigate moral discomfort. International humanitarian law is often presented as an ethical guideline.

However, in practice, it operates primarily as a bureaucratic framework for regulated armed conduct, specifying who may engage in violence, under what circumstances, and within which parameters. Hague law governs the methods and means of warfare, while Geneva law safeguards persons; together, they form the twin pillars of International Humanitarian Law (IHL).

Today, this rationalisation of violence through law is more sophisticated - and more insidious - than ever. But beneath these formal frameworks lies a darker truth - violence, however regulated, inevitably produces a choreography of human despair.

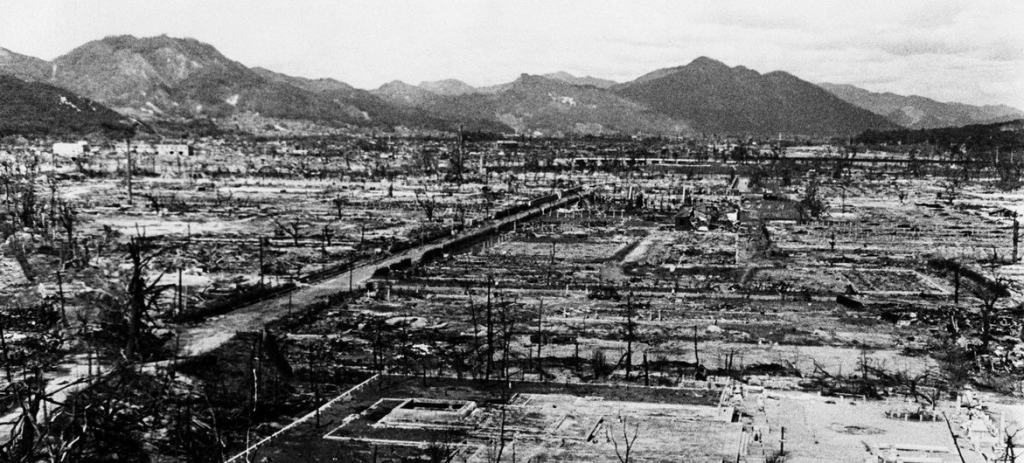

War as a Choreography of Despair and Debris

The ongoing conflict in Gaza highlights complex and often troubling dynamics. On October 7, 2023, the actions undertaken by Hamas were not merely responses driven by desperation or strategic miscalculations.

Still, they appeared to be deliberate choices rooted in a specific ideological agenda, which included the instrumental use of civilian casualties and abductions. Recognising this context is essential for an accurate understanding; minimising or dismissing these factors risks oversimplification and misrepresentation.

This conflict extends beyond conventional warfare paradigms. It involves a complex interplay between a recognised state actor and an entity that styles itself as one but binds itself only to martyrdom. Hamas is a hybrid: part government, part militia, part theological machine. The primary objectives are often more symbolic than purely territorial, emphasising resilience and ideological steadfastness over overt military victory.

In such asymmetrical scenarios, unconventional tactics—such as utilising civilian areas and casualties as strategic elements—are employed. When you lack tanks, bodies become weapons - turning human lives into tactical currency, a morally and legally troubling strategy.

Opposite Hamas stands Israel, often described as the only democracy in the Middle East, but also a state that systematically deploys legal reasoning to rationalise and escalate violence. Israel uses Charter-based self-defence to justify the resort to force, and IHL to discipline how that force is applied.

While these legal justifications may provide tactical advantages, they also raise questions about their impact on the foundational democratic principles, especially when applied to justify actions that result in significant civilian harm. Practices such as targeted strikes on densely populated areas under the guise of military necessity and the demolition of entire neighbourhoods have ethical and legal implications.

The use of legal frameworks to retroactively justify actions can blur the distinction between a necessary defence and a disproportionate response. In urban combat environments, civilian casualties have become a frequent and often unavoidable reality, reflecting the grim complexities of modern warfare.

The ratio of civilian to militant deaths in Gaza is horrific, yet, historically, not exceptional. From Fallujah to Grozny, urban warfare resembles organised slaughter more than any noble duel between armies. Disproportionality is not a mistake; it is built into the architecture of city-based conflict.

In Gaza, this choreography has evolved beyond mere physical destruction, weaponising human suffering itself.

Hamas and the Politics of Weaponised Suffering

In contemporary conflicts, the pursuit of truth often encounters significant challenges, as narratives become influenced by strategic considerations rather than objective facts. Data concerning casualties and damage from Gaza are frequently manipulated, exaggerated, or minimised based on the source, emphasising the importance of visual and rhetorical control in shaping public perception.

Both Israel and Hamas are invested in controlling the optics, aware that in this war, winning hearts and minds matters as much as military gains.

Judith Butler, in her thought-provoking book Frames of War, reminds us how societies selectively mourn their dead, constructing hierarchies of grief that define who is considered truly human. Lives become politically significant not by their inherent worth, but by the way their loss can be politically leveraged.

In the context of Gaza, the victims are used as symbols - Palestinian casualties evoke moral outrage against Israeli actions, while Israeli casualties are employed to justify retaliatory measures. This dynamic exemplifies what Butler calls discursive violence, where the dead are mobilised as rhetorical tools rather than recognised as individuals with inherent dignity. Humanity itself thus becomes a negotiable category.

Modern warfare unfolds on two interconnected fronts: the physical battlefield and the arena of public opinion. Both domains involve strategic communication, which is often influenced by victories and setbacks, leaving confusion in its wake once the dust settles.

Perhaps the cruellest irony is that truth itself has become negotiable, stripped of innocence, another piece of collateral damage in the choreography of contemporary conflict.

Despite these complexities, there remain choices and responsibilities that influence the course of events. Public discourse frequently implies that condemning Hamas's actions absolves other parties of responsibility, presenting a false dichotomy of moral clarity. In reality, conflicts involve multiple actors, and a refusal to seek peaceful resolutions can serve to prolong hostilities.

Yet the strategic refusal embodied by Hamas reveals a deeper fracture: the erosion of reciprocity, shaking the very foundations of humanitarian law itself. Hamas’s deliberate choices - such as refusing negotiations, holding hostages, and rejecting surrender - actively sustain Israel’s jus ad bellum argument for self-defence, leaving intact the legal frameworks that legitimise ongoing hostilities. In doing so, humanitarian law becomes less a tool of protection and more a procedural justification of continuing violence.

Reciprocity Shattered: Law at the Edge of Asymmetry

At the core of International Humanitarian Law lies an implicit assumption: mutual recognition. The established rules presume that all parties acknowledge a shared understanding of legal boundaries, even if their adherence is imperfect.

War, in this context, is not regarded as lawless chaos but as a temporary suspension of legal norms within agreed-upon parameters. However, when this mutual compliance breaks down, warfare ceases to be a regulated contest. It may evolve into a campaign aimed either at compelling the opponent to return to compliance or seeking to eliminate the opponent.

Law, without mutual adherence, risks transforming from a protective instrument into a liability. What is intended to safeguard all parties can become an undue burden for those who uphold the rules. Acts of restraint may be exploited as strategic vulnerabilities, while those who disregard legal norms can leverage moral obligations to their advantage. This is not merely a theoretical concern but a practical reality in asymmetric conflicts.

Groups such as Hamas do not simply violate IHL; they reject its foundational premise - that when facing inevitable defeat, surrender is appropriate. Yet, IHL binds organised armed groups, irrespective of state recognition; its obligations are absolute, not contingent upon reciprocity.

Historical examples like Germany’s surrender in 1945 and Japan’s capitulation demonstrate acknowledgement of such norms. In contrast, Hamas does not seek victory through conventional means; its objectives are oriented toward endurance and martyrdom rather than negotiation or capitulation. In such contexts, reciprocal legal frameworks collapse; there is no shared legal or ethical horizon, only the ritualistic performance of sacrifice.

Historically, the laws of war were designed to regulate conflicts between sovereign states that acknowledged one another as legitimate opponents. Even amidst total war, some shared vocabulary persisted—terms such as surrender, ceasefire, and negotiated terms.

In the Gaza context, that shared legal language has disintegrated. One party – Israel - is expected to operate within legal boundaries, while the other – Hamas - is fundamentally rejecting the very notion of bounded warfare.

This breakdown is not purely legal but ontological; it signifies a fundamental rejection of mutual legitimacy. Israel does not recognise Hamas as a lawful combatant; Hamas does not view Israel as a legitimate state. When mutual recognition disappears, the enforcement of law becomes futile; its invocation is often reduced to a ritual rather than effective accountability.

In such a vacuum, power dynamics tend to override principles. As Carl Schmitt observed, sovereignty is exemplified precisely in moments of exception—decisions about who must be sacrificed when norms fail to function.

Thus, humanitarian law risks becoming merely ceremonial, invoked selectively as a justification rather than universally as an obligation. When unilateral necessity rather than shared limits drives conflict, humanitarian law becomes merely instrumental rather than a mutual commitment. States still adhering to legal standards often do so for the sake of maintaining a positive international perception rather than engaging in direct dialogue with their opponents. Their legal restraint may serve as moral posturing rather than genuine engagement.

This fragile expectation of reciprocity is not only a constraint on conflict but also a binding connection between law and reality. Once mutual recognition is eroded, both sides suffer a loss of legitimacy. Democratic societies that demonstrate partial adherence to legal standards risk internal disintegration of their moral authority.

As they apply laws selectively, their legitimacy diminishes from within. What may be a tactical stance for groups like Hamas gradually becomes a form of self-inflicted strategic decline for those committed to legal principles. Despite this breakdown in reciprocity, the question remains: Does international humanitarian law still offer meaningful protection in a reality stripped of mutual recognition?

Thin Red Lines: What IHL Still Manages to Save

It is essential to recognise the tangible contributions of international humanitarian law in promoting ethical conduct during armed conflicts. Even in asymmetric conflicts, its principles have curbed the use of certain weapons, enabled humanitarian access, and created pathways, however narrow, for legal accountability. War crimes tribunals, protections for medical personnel, and the global stance against torture represent meaningful progress - a testament to a civilisation’s efforts to mitigate its violence.

Legal measures such as the prohibition of cluster munitions, protection of medical convoys, and the designation of no-strike zones have, in some cases, directly saved lives. While International Humanitarian Law can sometimes be inconsistent or selectively applied, it provides necessary procedural safeguards, such as delays, legal reviews, and strike cancellations, that can help prevent unnecessary harm. Although these mechanisms are not infallible, they serve an essential function in conflict mitigation.

Nonetheless, recent events in Gaza compel us to question whether formal legal adherence alone is sufficient to ensure moral legitimacy or meaningful protection. If legal compliance is pursued only when it aligns with strategic convenience, and if its moral authority is compromised when challenged, such adherence risks being superficial - merely a formal compliance rather than an embodiment of ethical commitment.

Compliance must extend beyond procedural formalities. Suppose parties involved view the law as merely a technical requirement rather than a moral obligation. In that case, it risks undermining its legitimacy and turning into a justification for actions that violate fundamental principles.

Under such circumstances, the law may cease to serve as an adequate safeguard against violence and instead become a nominal framework through which conflicts are managed. Relying solely on the appearance of legality can divert attention from the core ethical imperatives and moral responsibilities that underpin these legal standards.

Yet even as we acknowledge the thin red lines IHL draws, we must also confront how law itself has become complicit, structuring and authorising acts of destruction.

The Rites of Authorised Destruction

In contemporary warfare, legality does not simply prohibit violence; it formalises and systematises it. Protocols, checklists, and authorisation procedures serve to manage and monitor operations, ensuring that actions are conducted within structured, reviewable frameworks. This design renders the methods of action transparent, not for moral oversight, but for bureaucratic efficiency.

Walter Benjamin deepened this logic in his seminal 1921 essay "Zur Kritik der Gewalt" (Critique of Violence), where he argued that law does not abolish violence; it absorbs it. For Benjamin, law's violence is never absent - only masked by ritual and procedure. Every legal order, he wrote, is born out of mythic violence: a founding act of force that asserts authority, not through consensus, but through domination.

Once established, the law maintains itself through what Benjamin called law-preserving violence—police actions, judicial rulings, and military operations—all cloaked in the legitimacy of due process. Violence, in this view, does not disappear under law; it is simply naturalised, codified, and ritualised.

Actions that could be outright prohibited are instead incorporated into formal procedures: force becomes authority wielded through judicial or administrative channels, conflict zones are managed through legal protocols, and incidents are documented as case files.

Nowhere is this logic more starkly visible than in Gaza, where missile strikes are evaluated for legality, and destruction is documented systematically. The process follows formal procedures, with legal teams assessing proportionality, warnings, and civilian impact. The destruction proceeds according to established protocols, and their bureaucratic organisation often obscures the moral gravity of such actions.

In this context, ethical considerations are integrated into procedural assessments, such as determining the legality of targets, the adequacy of warnings, and the proportionality of harm, guided by metrics and documented evaluations.

While the voices of those affected may not be directly heard, their circumstances are documented and analysed through official records - an exercise in institutional assessment and accountability. Ultimately, the bureaucratic codification of violence demands that we look beyond legal formalities to the moral judgment only human conscience can provide.

Beyond the Ledger: Reclaiming Moral Judgement

Violence, regardless of its execution or documentation, cannot absolve itself of accountability. Even when every act is recorded and every quantitative detail verified, it still awaits a human declaration of responsibility: “This was carried out, and I am accountable.” Contemporary warfare—automated, data-centric, and legally regulated—tends to suppress that essential acknowledgement.

Legal frameworks, initially established to regulate the use of force, have increasingly become tools for its management. What once served as a boundary has transitioned into a procedural framework. In asymmetric conflicts - where one party adheres to established conventions and the other does not - the semblance of legality persists even as the true significance diminishes.

Reciprocity diminishes, and proportionality becomes a ritualistic formality. Acts of violence are filed away rather than critically examined. The core human element—judgment—that underpins political responsibility slows to mere calculation.

Philosopher Giorgio Agamben warned of a future where individuals are reduced to data entries—deaths recorded without genuine mourning or moral engagement. This is not a failure of law but its complete consummation. When violence is fully legalised, the moral weight of killing is devalued; actions deemed lawful no longer evoke moral condemnation.

Hence, the deeper horror behind the word genocide. Genocide is not an IHL violation but an international criminal offence (Rome Statute, art. 6), prosecuted irrespective of IHL “compliance.” Under Article 6 of the Rome Statute, genocide demands a specific intent “to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” Cities lie in ruins, neighbourhoods erased - yet the dossiers display no such intent, only compliance.

Every protocol observed, every order archived—no decree of annihilation, therefore no supreme crime—only devastation by design. The tragedy is not that the system malfunctioned, but that it functioned flawlessly. What should have screamed injustice becomes invisible precisely because it was done “by the book”.

This is where a new category perhaps demands recognition: not genocide in the strict legal sense, bound as it is to the burden of proving intent, but something that mirrors its outcome with unsettling precision. A slow-motion annihilation veiled in the sanctioned vocabulary of “necessity” and “proportionality.” What we might call Gazacide: the destruction of a people not through declared extermination, but through systematically tolerated methods.

Here, intent is not expressed as an explicit aim to erase a people but emerges as the foreseeable consequence of military strategies that produce mass civilian death, infrastructural collapse, and the transformation of a territory into a space unfit for life.

Gazacide names a condition in which the scale and nature of violence, comparable to the use of a nuclear bomb, are so overwhelming that the result becomes functionally indistinguishable from genocide. Not by design, perhaps, but by method. Not through stated ideology, but through the sustained erosion of the conditions that make collective existence possible.

Hannah Arendt warned that the gravest evils are not rooted in fury but in detachment—individuals following rules while refusing to examine their actions critically. Today, that detachment is increasingly automated.

Algorithms will soon evaluate targets, assess risks, and execute orders - never hesitating, never doubting, never asking whether the act can be justified. In their calculated silence, we will hear the echoes of our abdication of moral agency.

Actual endurance does not necessarily take the form of heroic resistance; perhaps that is a relic of a past era. What remains enduring is the act of remembrance - the deliberate refusal to allow memory to be replaced by metrics, to prevent deaths from being reduced to mere data points, and to stop the question of justice from being obscured by bureaucratic processes.

If responsibility still lies with us, it is to remember that law is a tool - an instrument - not a substitute for conscience. No system, however precise, can pose the one question only humans can ask: What ought I do?

Abandoning that question does more than simply failing to pursue justice; it fundamentally undermines the foundations of judgment and political life itself. And ultimately, that is a loss no statute, protocol, or machine can ever restore. In the end, legality without humanity reduces justice to mere accounting - when numbers replace names, no law can save us from ourselves.

I agree with you on the Gazacide part: the fact that everything is legal and planned (even in the case that the other party doesn't recognize international or national law) doesn't mean that the destruction in Gaza is a normal aspect of violence.

This should, however, call into question the violent organization that is the state itself. Laws, statutes, protocols clearly don't work where the state can legitimize its own violence, as the essence of statehood is a violent being, especially if this has happened so many times with the atomic bomb in Hiroshima, and in Gaza, and in Yugoslavia, and in the Soviet Union... Violence from states doesn't happen DESPITE there being laws, the system that we live under has violence BAKED IN. When Western countries were able to source out that violence through colonialism and imperialism, they had good days. Our reluctance on pronouncing the obvious - that the destruction of the nation state will put an end to this violence - leads to Gazacide somewhere in the world every couple years.