Since the collapse of the USSR, relations between Azerbaijan and Iran have developed in a “wave-like” pattern, characterised by periods of rapprochement followed by phases of sharp rejection. Despite obvious cultural, historical, and religious commonalities, deep distrust persists between the two countries, fueled by both internal and external factors. The last few years have marked a distinct stage in bilateral relations between Baku and Tehran.

By Alihuseyn Gulu-Zada

Following the armed attack on the Azerbaijani embassy in Tehran and the subsequent diplomatic crisis, the rise to power of President Masoud Pezeshkian—an ethnic Azerbaijani from the reformist camp—after the death of the ultra-conservative Ebrahim Raisi in an aviation crash in 2023, seemed to signal the possibility of a “reset” in the Azerbaijani-Iranian track.

Nevertheless, the positive dynamics in bilateral relations were not without incidents. In late December 2025, on the eve of the protests, Azerbaijan initiated an investigation regarding the presentation of the folk song “Sari Gelin” as “Armenian” during a broadcast on Iranian state television.

Historical Retrospective

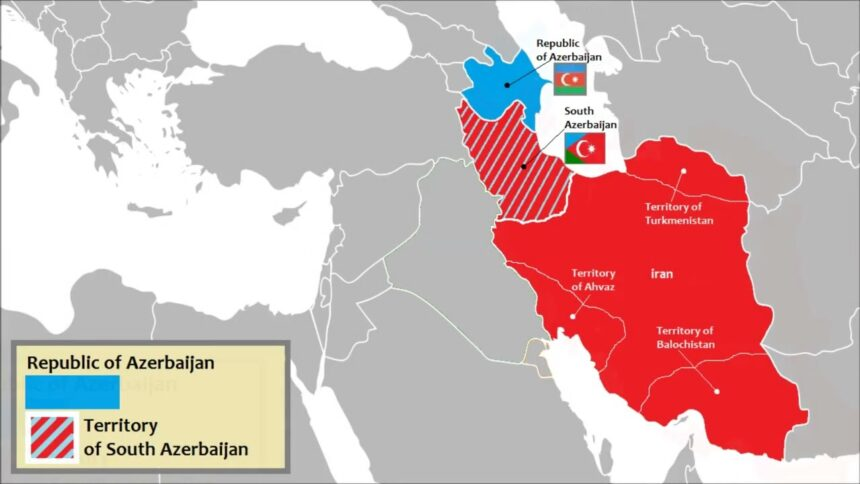

In general, Iran is not a “foreign” country to Azerbaijan. In the northern ostans (provinces) of the Islamic Republic—known as South (or Iranian) Azerbaijan—estimates of the ethnic Azerbaijani population range from 22 to 45 million; historically, they are referred to in Iran as “Tork.” Consequently, the recent protests in Iran in early 2026 have once again highlighted the geopolitical risks and security concerns for Azerbaijan

Furthermore, it is noteworthy that specifically Azerbaijani Turkic dynasties—from the Qara Qoyunlu to the Qajars—ruled the vast geography of Iran for several centuries. It is also interesting that practically every significant internal political event (including revolutions) in Iran that succeeded historically began in, or was directly dependent on, trends unfolding in South Azerbaijan.

This includes, for example, the Constitutional Revolution (1905–1911), the Azadistan movement (1920), the “21 Azer” movement (1945–1946), and, of course, the Islamic Revolution (1979), which, following the shooting of demonstrators in Qom, instantly spread to the territory of South Azerbaijan.

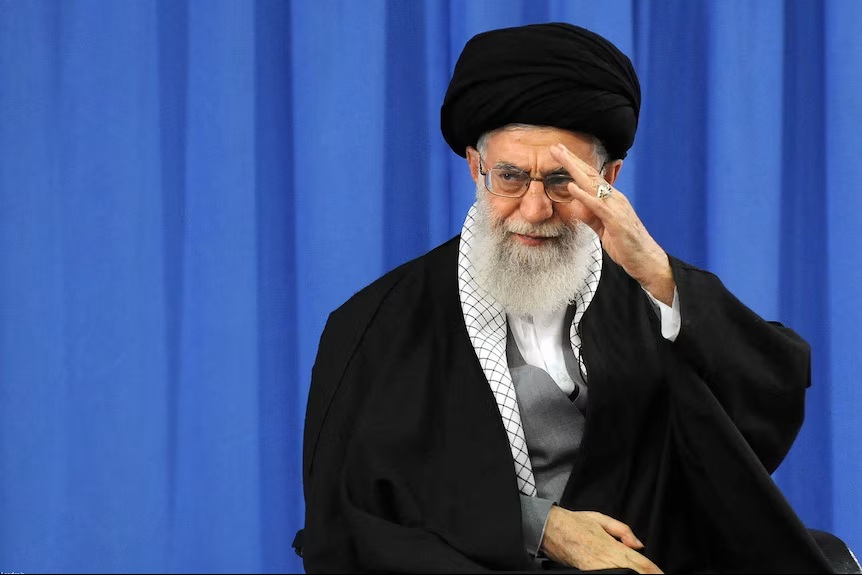

Remarkably, even the modern political elite of the IRI includes ethnic Azerbaijanis, including Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and current President M. Pezeshkian. Thus, this close historical tie makes Iranian internal instability a sensitive challenge for Baku.

While a significant number of socio-political forces sympathetic to South Azerbaijan’s independence remain in Azerbaijan, official Baku generally prefers to avoid popularising the issue. Regarding the recent protests, the Azerbaijani side did not manifest any aspirations, adhering instead to the principle of good neighbourliness.

However, the diplomatic “pause” adopted by Azerbaijan during the 2026 protests was not without symbolic gestures within certain groups in the Republic. Several local parties and NGOs released joint statements supporting the independence movement of Iranian Azerbaijanis during the escalation of the internal political situation in Iran. A rally was even organised near the IRI embassy in Baku to support and protect the independence movement of South Azerbaijan.

Baku’s Vulnerabilities to the Iranian Crisis

In reality, the hypothetical destabilisation of Iran represents both an opportunity and a risk with a dilemma for Azerbaijan. First, the scenario of Iran’s disintegration, while unlikely under current geopolitical conditions, threatens chaos at the southern borders of the Caucasian republic, creating direct security threats.

Second, Azerbaijan faces limited capabilities to respond to a hypothetical internal political crisis in Iran. Baku’s resources—religious-ideological, military, economic, and demographic—do not allow it to effectively influence the development of force majeure events in the IRI (without the support of external partners, primarily Turkey and Israel).

Third, regarding Turkey and Israel: in the event of maintaining a neutral position, Baku would have to play a “balancing policy” against Ankara and Tel Aviv for the sake of non-interference in Iran’s affairs, as the country would be under constant pressure from its allies.

Fourth, even in a full-scale escalation where the situation spirals out of control, Baku could face a humanitarian crisis and a mass influx of refugees, placing a severe burden on the country’s socio-economic system.

Geopolitical Risks and Security Dilemmas

Regarding specific geopolitical risks, Azerbaijan’s position is further complicated by the likely involvement of a conditional “US-Israel” alliance in a confrontation with Iran.

From Tehran’s perspective, the territory of Azerbaijan is, and will be, considered a “Zionist outpost” on its northern border. This makes the territory of the Caucasian republic a potential target for preemptive strikes by the IRGC under the pretext of “protecting national security,” even considering the risk of a direct clash with Azerbaijan’s strategic ally, Turkey.

Although the highest Iranian military-political leadership, including the IRGC, did not explicitly name Azerbaijani territory as a “legitimate target” during briefings amidst the recent protests, one cannot rule out such a scenario in the event of US strikes on Iran. This is particularly relevant given that the Islamic Republic has conducted several military drills on the border with Azerbaijan in previous years.

Additionally, such an existential escalation in Iran directly threatens Azerbaijan’s critical infrastructure—oil pipelines, communications, and transport corridors, including the Caspian basin, where strategic (maritime) routes lie within the context of the “Middle Corridor” (TITR).

Finally, the hypothetical threat of full-scale hostilities between the US/Israel and Iran carries economic risks for the Azerbaijani side. In the event of military escalation, Azerbaijan risks losing foreign investors and/or a slowdown in the implementation of large-scale geopolitical projects due to a deterioration in the investment climate.

Destabilisation in Iran could paralyse the implementation of strategically important projects and call into question Azerbaijan’s role as a transit hub between Russia, the Middle East, and South Asia, potentially turning the entire Middle East and South Caucasus into a “grey zone.”

Conflict of Interests and Mutual Dependence

Paradoxically, mutual dependence makes conflict between Iran and Azerbaijan undesirable for both sides. Despite a long history of tension, Baku benefits from Iran’s stability, primarily by helping ensure the predictability of its southern neighbour in economic cooperation and strategic balance in the South Caucasus.

For Iran, although Azerbaijan remains a “controversial” country and a geography of religious-historical grievances, it serves as a necessary partner. Tehran has (forcibly) accepted this in the context of the new geopolitical realities established after the Second Karabakh War.

Recently, Azerbaijan has solidified its status as a pivot state, providing countries across the vast Eurasian geography access to essential transport routes and acting as a “buffer” between Iran, Russia, and Turkey. Therefore, despite contradictory rhetoric, practical interaction between the two countries retains stability in the South Caucasus region.

Azerbaijani-Iranian relations are an example of a complex balance between historical proximity and geopolitical distrust. Any weakening of Iran, contrary to the expectations of certain non-governmental Azerbaijani patriotic circles, may not strengthen Baku’s position but rather pose security threats and economic instability.

In the near term, Azerbaijan must maintain a fine line between protecting national interests and avoiding being drawn into regional conflicts (including within Iran). Such attempts by the West have already occurred in the context of the possible deployment of an Azerbaijani contingent as part of a peacekeeping mission in Gaza.

Ultimately, strategic restraint is not a manifestation of “weakness” for Baku; on the contrary, it is the realistic choice of a country situated at the crossroads of important routes and the interests of Great Powers.

Alihuseyn Gulu-Zada is an independent analyst and researcher specialising in geopolitical processes, risk dynamics and security, as well as the history of the South Caucasus and Iran. His research interests include the peace process between Armenia and Azerbaijan, domestic and foreign policy trends in Iran with implications for the Middle East, and Russia's and Turkey's external vectors in the South Caucasus. This is his first contribution to The Liberum.