Something I tried to grasp in my book Be Abyssal is the acceleration that modernity has brought into all human relations. In the past, relationships grew slowly and evenly; village communities followed the rhythm of the seasons, and one’s circle of acquaintances was limited to what could be reached on foot. Deepening contact took years. It is the world of Pride and Prejudice and Wuthering Heights.

By Sid Lukkassen

Today, by contrast, everything moves at lightning speed. The internet opens an inexhaustible pool of strangers: within days, a connection can become intense, emotional, or sexual – only to evaporate just as quickly. Not only intimate relationships but also work relationships are increasingly fluid: temporary contracts now structure professional life.

Meanwhile, matters that were once self-evident – food, sex, climate – have become ideologically charged. You go out for a pleasant meal, and what ends up on your plate is already a political statement. Vegan or not, halal or haram, insects, palm oil, and so on.

This is what I mean by acceleration: the molecules of social life, once anchored in tradition, are now brought to the boil under ideological tension. The basic building blocks of existence are injected with ideological energy; everything becomes volatile. People look for new anchors and find them in bubbles and echo chambers.

Anyone attempting to engage in substantive debate with an unwelcome argument is blocked. Preaching to one’s own choir is all that remains, and society becomes ideologically overheated.

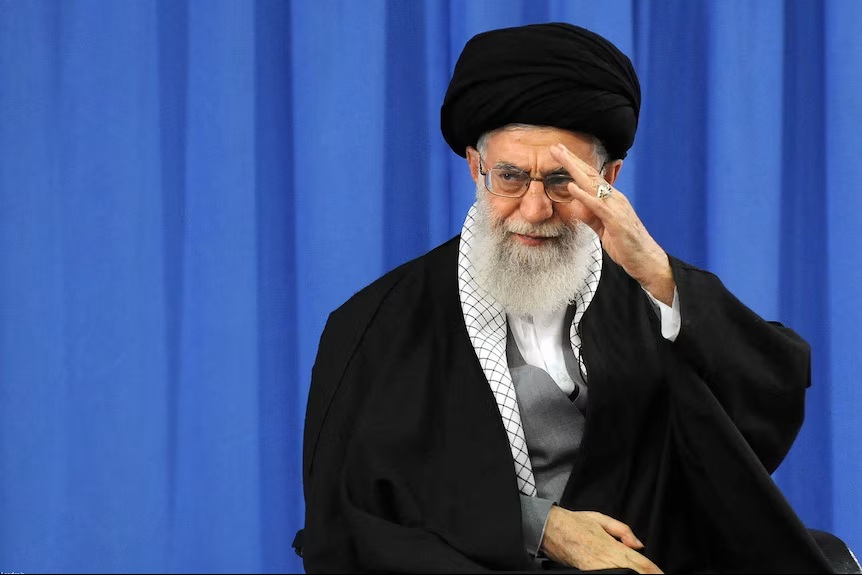

There is also a historical difference in how authority is viewed. In Asia, power is traditionally top-down; the emperor is the centre. China transferred that role to the Communist Party, and Russia today to Putin.

The West, by contrast, descends from loose tribes of Germanic peoples and Vikings who moved along creeks and bays. They went where they wished – Caesar described it already in The Gallic Wars. For two millennia, Germany was a patchwork of tribes and duchies; only a century ago did it become a nation-state.

In the Middle Ages and early modernity, this popular spirit was articulated in documents such as the Magna Carta, the Blijde Inkomste, the Plakkaat van Verlatinghe, and various Bills of Rights. Always, the idea was that sovereignty rises from below: the sovereign serves the people and is accountable to the lower layers.

The individual possesses inalienable rights over body, property, and freedom; if these are violated, revolution is justified. Republicanism, liberalism, and the rule of law have their roots here.

Yet, with modern technologies, an unintended consequence occurred. People who wished to be left alone, wanting sovereignty in their own circles, suddenly had to relate to overarching structures. These were inherent to the new economic conditions. Before mass society emerged, more than 90% of people worked in agriculture; the rhythm of the seasons provided order and stability.

But soon, vegetables were imported, a 24-hour economy appeared, and Ricardo’s comparative advantage took hold. Economic relations became extremely complex and frantic. The individual felt lost and alienated. By now, not only has the worker become alienated from the production process, but the production process has also become alienated from the product. Western economies spend more time on marketing and PR than on making anything tangible.

This lack of stability and security fuels the call for strong leaders, but the issue runs deeper. I think of a discussion with Willem Engel, who defended classical fundamental rights as protection against state power. My reply was that the communicative structures themselves – the infrastructure of social existence – reinforce totalitarian tendencies. The very way information circulates already centralises power.

On the internet, almost everything is collective. You do not walk to the local pub to hear the latest gossip; no, influencers with ten thousand followers push you to like or denounce someone. Before you can think for yourself, a topic is already ideologically framed.

The implications are tribal: everyone is simultaneously sender and receiver, and everything is locked into networks.

The same applies to platforms like Twitter and YouTube. You can build a tiny platform of your own, but you will reach only a fraction of the audience. Financial incentives push everyone toward regulation and conformity: status and income depend on visibility. Anyone who wants to defend classical freedoms seriously – call it “Magna Carta England” – will inevitably collide with nearly all institutions, Big Tech included.

Collectivisation is already deep: witness how readily the masses embraced QR codes. I saw Amsterdam cafés with signs reading “we do not accept debit cards,” as if they were anarchist pirates evading the tax system, while simultaneously requiring visitors to show QR codes.

This homogenisation – the post-industrial service society that shapes the characterless mass-man – is in itself already fascistic. A bureaucratic machine that sustains its own complexity while crushing the individual. In the Netherlands, the Toeslagenaffaire was the definitive proof.

It could come this far because classical conservative ideologies are powerless against four developments: unlimited money creation since 1913; the mass production of artificial fertiliser (and gunpowder), which eliminated the Malthusian population cycle; the energy from oil and gas that allows rapid movement of goods and people; and the computer plus the internet, which further dehumanise everything. In short: the total acceleration of life.

I recall a friend in Brussels, a convinced conservative journalist. We often discussed immigration and the EU. I pointed to the fatal combination of modern transportation, white cultural guilt, the profits of the human-smuggling mafia, and the behaviour of EU member states that throw problems over each other’s fences and merely reprimand Salvini or Orbán. He would say I was too pessimistic, that leaders were already working on it, and that he felt “a duty to be optimistic.”

But when the asylum crisis reached the hotel in Albergen, my analysis proved correct. I could think ahead, whereas classical conservatism had no answer to the mass-scale conditions of modern existence.

Giorgio Agamben writes in Homo Sacer that fascism and Nazism are, above all, new definitions of the relationship between the human being and citizenship. It is precisely this total acceleration, this mobilisation of the entire life-world for a political purpose, that distinguishes them from conservative authoritarian regimes such as those of Pinochet or Franco.

The conservative dictator says: live your life, but stay out of politics. The fascist abolishes the distinction between the private and the political: the whole of life becomes a matter of the state.

Thus, we arrive at left-wing identity politics, which ideologises private life and thereby mirrors fascism. Sexuality is no longer a private matter but a collective identity that must be publicly celebrated. Pride parades are attended by politicians under the pressure of woke norms. Anyone who wants none of this is, through the totalising nature of modern conditions, either crushed as a conservative or forced to participate in the same totalising logic, but then in the opposite direction.

In summary, modern conditions have destroyed the classical aristocratic society. The conservative maintains a distinction between private life and public political life; the left rejects this distinction and radicalises everything. The left uses state power to make its culture the culture of all: consider the banning of meat meals or meat advertisements. If the right allows itself to be pushed back into the private domain, it loses. The right must fight for the public domain with all its might.

Roger Scruton, once a mentor to Thierry Baudet, has been almost forgotten less than two years after his death, because his conservatism no longer fits the modern reality of artificial fertiliser, supermarkets, overcrowded cities, fiat money, and digital networks. Classical conservatism arose from aristocratic traditions but was already nostalgic at its birth.

You can support me: Sid Lukkassen.