“And when you get to Belgium… pursue your dream! Love! Be yourself!” I said to Mohamad, a Palestinian refugee whom I met on the island of Chios, Greece. We babbled on and on about the importance of freedom until he smiled with the politeness of an Arab host who prefers that his guest overstays his visit than ask him to leave. “Freedom is great,” he said. “But more important is justice.”

By Rayyan Dabbous

His answer gave me shivers because I sensed where the conversation was heading. I had just read Albert Camus (“absolute freedom mocks at justice, absolute justice denies freedom,”) and I knew this young refugee would sum up in five minutes what the French author fleshed out in five books. And he did.

What a limbo. I could not convert Mohamad into the apostle of free love, championing choice over duty, nor could he convince me that justice – that awful law of the many – had to be defended at any cost.

I was an Arab from the shackles of society; he was an Arab whose society was broken by the same swords that slashed my chains. Even the Arabic language we spoke marked the conflict: we often say Nahna (We) when we only mean Ana (I). My outraged I could never identify with any We. In the same way the We that so long protected Mohamad felt outraged by any intruding I.

History lesson

When did this misunderstanding between Mohamad and myself begin? A quick history lesson. The modern conflict between freedom and justice, the singular and the collective, finds its roots in the French Revolution.

The preaching of freedom during the Enlightenment ended the unfair justice of the king – a fantastic feat until the bourgeois revolutionaries became conservatives overnight when they claimed their right to property. Possessions were not the chief problem – it was the greed that claimed them, and greed, like other abuses in capitalism, ironically originated from a noble chant for freedom.

Freedom caused injustice. As it does today: in my native Lebanon, amid corruption, we know that when the singular shouts “I won’t!” – the collective’s “we want” gets pushed aside.

But Mohamad and I are both Arabs! What does the French Revolution have to do with our heritage? I asked the same question to Naila al Atrash, a Syrian director, with whom I was discussing the East-West tension over individualism.

“You forget,” she said, “that postcolonial theory was originally an offshoot of Marxism.” She was right – I remember reading Rosa Luxemburg, and her insight that capitalism did not crash by itself as Marx predicted because of the time (and resources) colonialism bought for it.

Al Atrash also once explained to me the marriage between capitalism and colonialism in the Middle East of the 1920s; how an alliance with Arab patriarchal structures served local capitalists and foreign colonialists alike.

Civilization and its Discontent

Here I was running from the clutches of the patriarchy, and Mohamad from the aftermath of colonialism – and yet these two thieves partied together in our homes a century ago! More and more we begin to understand the conflict between freedom and justice as a global phenomenon.

It is not as a clash between two civilizations, East or West, but as the very triumph of civilization.

For Sigmund Freud diagnosed Civilization and its Discontent, and it was Lou Andreas-Salomé, his Russian colleague, who found that man, once civilized, will lose the original instinct to see two things as the same.

Freedom and justice could be the two faces of the same coin, and yet for Salomé, herself a Russian who stood between East and West, civilization mandates us to distinguish them as two different currencies. Similarly, Freud’s Oedipal Complex, despite its misuses, rightly showed that growing up – becoming a (civilized) man – means for the boy to lose something; in the psychoanalytic case, to relinquish his love for his mother.

Yet we also describe nature as motherly, and I wonder whether civilization, too, struggles because it had to prohibit to itself the love of nature; meaning, the love of being connected to everything; the seas and the forests, the wind coming from the West and the sun rising from the East.

When did modern civilization itself ‘grow up? With the Renaissance, and yet that intellectual revival would not have been possible if it were not for the Arabs who preserved and expanded upon the knowledge of the Greeks.

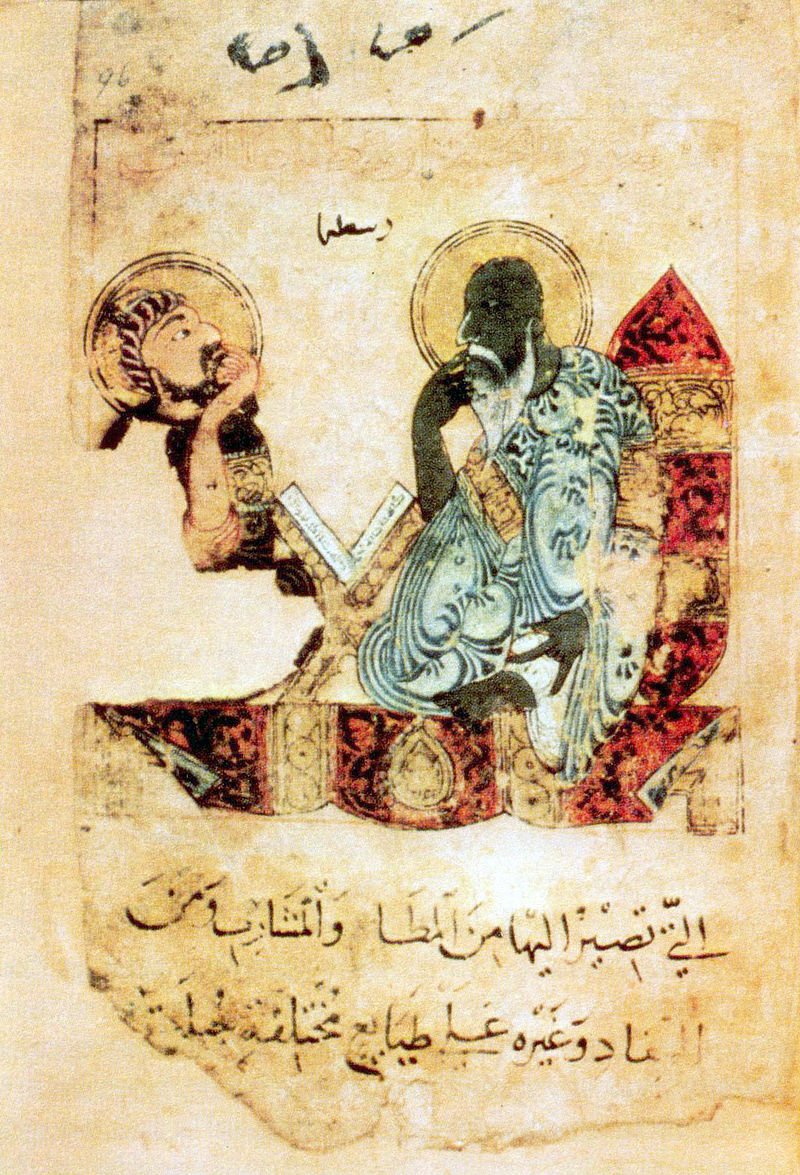

“Who killed the mother of civilization?” I asked as I inquired into how precisely the Arabs handed Europeans the keys to modernity. Ibn Rushd, or Averroes (d. 1198), was the last in the line of Arabic philosophers who worked out the thinking of the Greeks. By the time his works were read by Thomas Aquinas (d. 1274) who ushered Europe into the Renaissance, all his interpretations and innovations were accepted by the Italian – except for one theory.

Ibn Rushd sought to fully understand Aristotle, and he found that only one notion could help him accept free will within an Islamic-Aristotelian edifice: the idea that, in the end, we all had one common soul.

There was no other way to explain human behavior – it had to be that, otherwise Aristotle was wrong about everything else. Aquinas did not think so: versed in a Christianity that promoted the immortality of a personal soul, he could not accept this specific interpretation in Ibn Rushd. So Aquinas dismissed it and proceeded with the rest. But did the omission not carry a fatal flaw?

We are free only when we are together

Eight hundred years later… the contradiction Ibn Rushd warned us about managed to haunt the conversation between Mohamad and myself. It haunts us all… for as I write this article, Ukraine, that middle ground between East and West, is the latest victim of our dismissal of Ibn Rushd. For the Arabic thinker meant: ‘We cannot be free if we are not also bound in some way to others.’

That sounds like a contradiction to us modern readers… who assume freedom can only mean a life unrestrained and without borders, who forget that intruding upon the freedom of others means to relinquish our own.

Ibn Rushd reached his insight because he lived in a time when East and West could still feed on each other; when Cordoba could not have been an intellectual hub without Athens and Damascus, or rather without the Athens of Damascus.

The more I roam down the alleys of history, the more I find isolated voices that also reached a similar cosmopolitan insight as Ibn Rushd. Spinoza (b. 1632). The latter who could combine his Latin readings with his Hebrew background, also found that the I and the Other must be tied together.

Goethe (b. 1749), after the suicide of his first character Werther, had to flock to the Persian poet Hafez to write poetry that no longer found antagonism between life and death – since life, when conceived in the collective, could never die. Rilke (b. 1875), too, would have to travel to the depth of Russia to find relief from the individualism of European culture and to embrace a Russian God that, like Spinoza’s, could only exist if he existed everywhere.

It is no coincidence that most of us know Descartes and not his contemporary Spinoza because the former’s I think, therefore I am remarkably represent modern individualism. It was Descartes who lingered with us not Spinoza, in the same way, Napoleon triumphed over Goethe, and World War I overshadowed Rilke.

That also means we were left with the contradiction, with the nonsensical notion that we are free only when we are by ourselves. Such an egoistic stance could never accept that, somehow, somewhere, despite how we distinguish ourselves, we are all the same. And that is the goal of justice: to restore fairness, which is for the mother to refuse to favor one child over another; to tell them both, ‘but children, you are all the same.’

This act of reparation between sons – would it not restore the mother we lost as a civilization? Do we not all feel victims of an irreparable fissure between the favored West and the less favored East?

Samir Kassir

“Victimhood is the price of the defeat of the universal, rather than a product of the status quo,” Samir Kassir wrote sometime before he was assassinated, “the ideology of the moment preaches a refusal of the universal.”

An intellectual like Kassir could believe in the universal only because he could also cite in the same essay Friedrich Nietzsche and Ahmad Shawqi. I cannot think of any line from Ahmad Shawqi – but my Palestinian friend, Mohamad, certainly could. In the same way, I can remember how Nietzsche said that one should seek freedom, and then liberate oneself from emancipation.

Is it not our problem; that we still have not liberated ourselves from the shackles of freedom? We leap two steps forward when we rightly demand freedom – but once the dust has settled, should we not take one step backward?

That step backward – is it not a reparative act of justice? Is it not what Mohamad asked me to do… to take a step backward… when in my chant for freedom I forgot justice? Is justice than not the policeman over freedom but its final judge; in some way it’s a historian, who must look back and see where its abuses have leaked?

Practically speaking, Europe’s diverse refugee populations, the depositors of the knowledge of the East, must be allowed to be judges – as harsh as Montesquieu’s Persian Letters. Here lies the challenge Europeans must accept: to be judged by the very visitors for whom the hosts assume to be doing a favor.

Yet the honor, as Arabs commonly insist, comes from the guest, not the host. “A prophet has no honor in his own country,” the Bible also tells us, suggesting that migrants – these prophets! – themselves carry the good news of paradise to Europe.

It is the same with Europeans who travel to the East, and who bear with their ways of life that make their new hosts uncomfortable. But rather than cheer for cultural relativism, we must sit instead with that discomfort and resolve our relationship with it.

Kassir is right that the ideology of our modern times preaches a refusal of the universal. Yet in the universal alone can freedom and justice nest together – for when the Tower of Babel collapsed, we stopped working together toward a common objective.

We ended up each speaking a language of our own – culture to culture, but even person to person – and the result is our lack of agreement over basic human rights, especially related to gender and sexuality, two notions over which we would like the line to be drawn between East or West though there is enough chalk to draw a circle that joins us all.

In Lebanon, as in elsewhere, the West is blamed for too excessive of freedom, the East for too cruel of a justice. Yet those of us who leave Lebanon for the West will long for a justice we never met in person, and we will curse freedom we never exercised among people.

Can you blame us? In our lands, we could meet freedom only when alone, justice only amid others. But we ought to do like The Prophet of Gibran, that migrant, that prophet, that migrant-therefore-prophet, who amid his geographical disorientation could still write in America that “a single leaf turns not yellow but with the silent knowledge of the whole tree.” Meaning – nature knows how to balance freedom and justice, for while an individual branch freely moves away from the trunk, the light it receives belongs to All.

Harmony – harmonizing the waves of freedom and the seas of justice, the desires of the self and the needs of the whole –is what a world crippled with conflict needs above all else. Yet we must understand scientifically what harmony entails, how it can be that the healthy human cell, which knows no West and no East, freely subsists from our nutrients without jeopardizing the needs of the organism. Is cancer not cells abusing freedom, forgetting justice?

Let us then fight the cancer of civilization! And we can succeed only if we revive that maternal instinct we repressed long ago, the call for action that arises in the distressing thoughts of our children long before we begin to think of ourselves.

Rayyan Dabbous is a Lebanese author based in Toronto, Canada. His recent work includes DIY Creative Activism (2019) and Psychoanalysis of a Teenage Novelist (2020).