You are no doubt familiar with the ‘simulation’ theory of the Charlie Kirk assassination, again in comparison to the movie Snake Eyes (1998), with the neck shot, name similarities and even the date of murder.

By Emad Aysha

First, there are demons operating behind the scenes, and now a predictive programme. By contrast, I’d say that the planners of the hit took advantage of these pre-existing American anxieties by deliberately picking a patsy with the correct name, matching him to the target given the names and dates in Snake Eyes.

Americans have been on edge about pre-programming since The Matrix (1999), and that movie itself got its inspiration from Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation (1981). As luck would have it, I just watched a peculiar French movie that foregrounds it all – Eden and After (1970).

BACKGROUND CHECK: The real hero in ‘Snake Eyes’ (1998) isn’t Nicolas Cage but Brian De Palma, using posters and adverts to break the monotony of the American audience.

The story, so far as there is one, is about a group of disaffected French university students who hang out at the Eden café. They’re have nothing better to do, or believe in, than plot and scheme against each other. This includes everything from rape to murder. (Talk about lost innocence in the Garden of Eden.)

The waiter there also gets them drinks laced with drugs, and a mysterious outsider, a Dutchman, challenges them to leave the café and venture out into the wider world. He’d lived in Africa for decades and tempts them with tales of the mysteries of that place, along with the continent’s exotic drugs. But, and this is the question, is any of this for real?

You see someone trying to poison the narrator, Violette (Catherine Jourdan), only to get poisoned himself, and then we see him again later on, alive and well. An instance of Russian roulette, where someone gets shot, is then followed by the claim that the gun wasn’t really loaded. The Dutchman is also found dead at one point, on the shoreline, only to die in essentially the same way later in the movie, on the Tunisian shoreline.

Is any of this actually happening, or is it all role-playing? People here have prescribed roles and they are playacting their parts whilst pretending to be rebelling, political and sexual. Even when they go to Tunisia, pursuing a priceless painting that Violette inherited from her uncle, and kill, torture or maim each other, nothing comes of it. They all end up back in France, at the same café, waiting for a new, mysterious stranger to come and liven things up for them again.

France is a country of etiquette, showmanship, and pretence, and the young in particular are anxious because they live in a country that has lost its purpose following the loss of its empire. They’re stuck in a perpetual loop of just doing what society tells them to do, when they are supposed to be rebels, taking their anger out on each other instead of the powers that be.

The café, not surprisingly, is a modern monstrosity, made of glass and steel, and so affording you no privacy, with a very evident Coca-Cola sign in the background. Cultural colonisation by America in such a quintessentially French place, the café, where so much of the country’s philosophy, art and culture was once done. Mirrors and silhouettes add to unreality of it all.

CRASH TEST DUMMIES: The youthful residents of Café Eden are in a prison of their own making, downgrading both themselves 'and' their country’s heritage.

The painting they’re after is that lost heritage that they have reduced to a financial dream. Not coincidentally, it depicts a home in Tunisia, juxtaposed against the ferociously blue sky, painted in an abstract style. It’s a window on the world, the old world if you will, where life is more challenging but more meaningful, and much more real.

Alas, it’s something they can never attain. In one critical scene, you have the lovely, delicate Violette dancing at night to a raging campfire in the Tunisian desert, and she’s wild and captivating. It’s the same dance she did in France, at a disco, but so alive and vibrant. But then she gets kidnapped by her so-called friends.

When she escapes, almost dying of thirst in the desert, she’s rescued by a girl who is nearly identical to her – same complexion, build and the same clothes that resemble snake skin. More sameness, with the trap they’re trying to escape being on the inside of them.

A rape scene in the café also has this impression of no escape, along with a scene at an industrial complex that keeps Violette from getting to the French shoreline, back to nature. One character talks about the number 8, a clear symbol of infinity.

LIP SERVICE: A clash of stereotypes, with Pierre Zimmer as the Flying Dutchman and Catherine Jourdan as the Frog Princess?

This is more extreme than the plot twist in Matrix Reloaded!

And the Americanisation and mechanisation on display tell you this cultural miasma actually originates in the USA. Americans are the "jukebox generation," not to mention the TV generation, with commercials, sitcoms, and soaps telling them what to do, wear, believe, and eat.

Check out this sci-fi conspiracy thriller for measure – Michael Crichton’s Looker (1981). The hero is a plastic surgeon (Albert Finney) who is a suspect in some apparent suicides of models he’d worked on. Turns out they were murdered by advertising execs (James Coburn and Leigh Taylor-Young) that digitised their bodies and faces (with laser tech) to make computer replicas of them.

The commercials also hypnotise people subliminally, a metaphor for the more regular TV brainwashing of yore. The closing action sequence features the computerised models doing advertisements on screen while the hero is in the studio, gunning down the bad guys, with the invited audience watching and laughing.

On a less humorous note, the weapon the company produced to kill the girls is a ‘light gun’ that paralyses you momentarily, making you lose your sense of time and allowing an intruder to attack you. One girl is killed this way while driving a car on an open road, and the same almost happens to the hero.

VICTIM OF BEAUTY: Susan Dey as Cindy Fairmont, the next target in ‘Looker’. In a penultimate scene her father ignores here while watching a sitcom for cheap laughs.

Hey, isn’t that what happened to Princess Diana and Dodi Al-Fayed? Witnesses said they saw a mighty light, like a flash, that apparently blinded or disoriented the driver, causing the fatal crash.

Here’s a possible connection: directed energy weapons (such as pulse, RF frequency, and microwave energy burst weapons) have been used for crowd control (à la Blue Thunder), in this case on January 6 in the USA. (See Redacted, 11 January 2025). There’s a whole range of such weapons, including sound weapons. Spy applications of this technology have led to incidents such as memory loss.

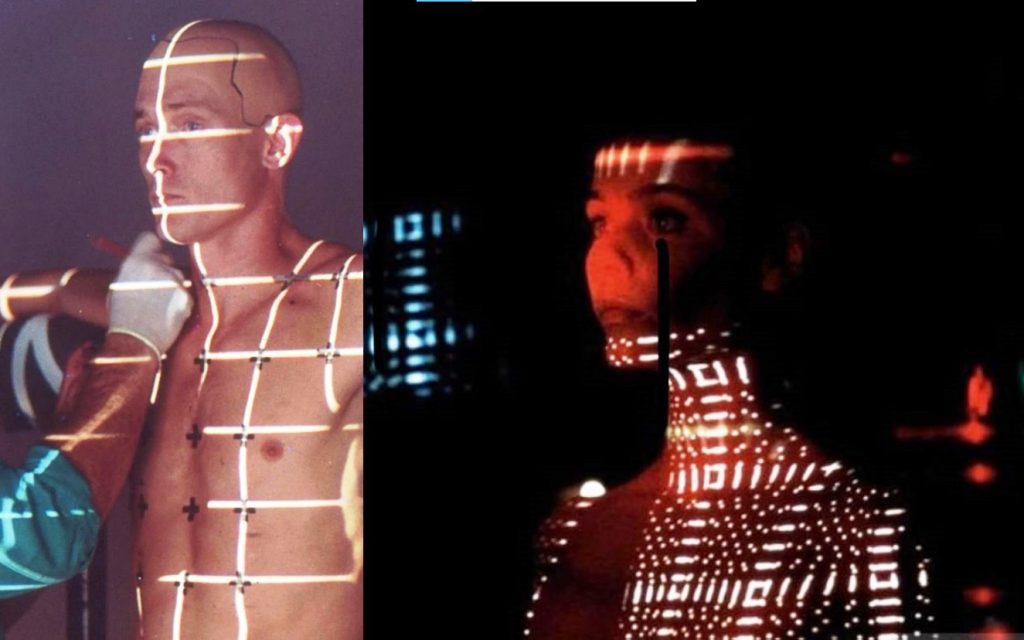

AI has also altered our perception of reality, as seen on the TV screen, making everything feel like a simulation. (This was before the polymorphing technique used in T2: Judgment Day, incidentally, with Robert Patrick also measured with laser lights).

The girls in Looker are picture-perfect, but they don’t receive the attention they need, so they feel they’re never good-looking enough. Similar themes abound in Eden and After, with girls who appear to have been painted by the same brush.

MADE TO MEASURE: Behind the scenes in ‘Terminator 2’, ahead of the times in ‘Looker’. (Even men in this future world men have to ‘fit in’!)

What happened to Kirk then is psych-warfare 101, made for an American audience too accustomed to being overwhelmed with data from the internet, and dopamine, uncritically. Thank heavens SF, and surrealism, are always one step ahead.

It’s that critical peephole into what actually happened in the past that can help us move, unencumbered, into what should happen in the future!