By Gouthama Siddarthan* --

Speculative fiction has, of late, been catching up in the world of writing which is highly enamoured of it. But there is a great danger of this fascination falling into the groove of popular legal thriller. The danger bristles with the risky possibility of toning down the high seriousness of this genre. For, underlying the speculative fiction writing is a popular thriller quality which has been exploited ad nauseam by the mainstream cinema and pulp fiction genre to the point of creating a cheap literature. This holds good for all languages, I think.

This third-rate trend of unfolding scenes of horror through the media of cinema and literature and thereby sending shivers down the spine of the audience has created a mindset steeped in all kinds of stereotypical terror and horror. It is only when one perceives the difference between the concrete scenes and the abstract feelings that they arouse in the minds of the onlookers that he can understand the distinction between sublime art and cheap trend.

What is ideal is that scenes in a horror film are crafted, penetrating deep into the higher artistic sensibilities. A film is not just a phantasmagoria of scenes after scenes flatly unfolding; the momentary and transient feelings of panic that they arouse are not those of real horror; they are the kind of third-rate cheap trash creating just moments of titillation or illusion.

Generally, horror films are not measured against the touchstone of world art film. The critics, by and large, pigeonhole horror films as second-rate or third rate ones. But this general trendy perspective was broken to pieces by Mexican film director Guillermo del Toro who metamorphosed the aesthetics of horror into a great art. I have a fancy for Toro who has declared, “Rather than terrorizing the viewers, my film sets out to put forward horror at its aesthetic best,” and whose recent work, ‘The Shape of Water,’ takes the cake in his celluloid philosophy.

Similarly, Werner Herzog’s ‘Nosferatu the Vampyre,’ based on Bram Stoker’s Dracula story, is a horror film of highest world standards. Klaus Kinski, who acted in the film, sucked the blood of critics, breaking the myth they had created that horror films are not art films.

Equally important is Japanese director Masaki Kobayashi’s film, ‘Kwaidan’, based on the Japanese folk tales.

Generally, standard horror films of art take their sustenance from the folklores of respective countries. Hollywood films which do not have such a background stoop to the mean level of cheap popular horror genre.

This perspective of horror at its aesthetic best can be applied to the world of letters too.

From Bram Stoker’s Dracula to Italo Calvino’s collection of Italian folk tales, this perspective can be applied and studied. In Calvino’s ‘Fantastic Tales,’ Ivan Turgenev’s ‘The Dream’ touches the zenith of artistic horror.

Now over to our native Tamil folk tales! They have the power of blood-churning thousand times more tremendous and fascinating than the archetypal Dracula.

For instance, lend your ear to our story of ‘Pangachi’ which revolves around a piquant and peculiar spirit.

The age-old tale goes on as follows:

When a girl attains puberty, an aromatic liquid called ‘kanthima’ flows out of her genitals; to suck the odorous liquid, ‘Pangachi’ lures the maidens, drains them of the life-giving liquid and ultimately, the maidens die, totally dried up and depressed.

The maiden is endowed with that pleasantly smelling liquid only for seven days after she attains puberty, which cannot be enjoyed by humans, but only by ‘Pangachi.’ That is a liquid of rare aroma, which has the power of enticing and enslaving any girl who happens to sniff it, if a man permeates his physique with it and approaches her. A magician, who comes to know about this, sends ‘Panganchi’ to suck and bring what is traditionally known as ‘kanthima.’ How the heroine in the tale thwarts this plan and escapes traps, killing and burying the sinister ‘Pangachi’ in her own genitals makes an interesting read. The horror knots powerfully evoked in mysterious and mesmerizing words can dwarf even the most inspiring story ‘Perfume’ written by German writer Patrick Süskind. This is my assessment based on truth.

Edgar Allen Poe, father of horror literature who gave a literary and artistic status to this genre, has stirred in me a powerful sense of panic unlike that evoked by any other. In his writings, no ghost, no goblin either struts about, scattering dark tresses of hair about. Yet a sense of horror permeating his writings sends chills down the spine of the readers.

Similarly, from my perspective, Carlos Fuentes’ short fiction, ‘The Doll Queen’, in some sense, belongs to the literary horror genre. (In fact, I am yet to read his novel, ‘Vlad’). Likewise, Gue de Maupassant’s stories such as ‘The Horla’ can be categorized as supernatural horror stuff; the dark ambience, the inner turmoil, the swelling emotions of the hero are captured in an extraterrestrial style branded by critics such as Lovecraft as unparalleled. (By the way, Horla is a French portmanteau of ‘hors’ and ‘la’ meaning ‘outside there’).

The origin of horror stories can be traced back to Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus’ published in 1818. The hideous, sapient creature she created in an unorthodox scientific experiment over the years became a horror archetype or myth. Keeping mind sci-fi writer Brian Aldiss’ comment that the novel should be considered as the originating point of horror literature, we can realise that the writings of this genre have several dimensions.

In this context, we can recall the modern horror novel, ‘Frankenstein in Baghdad’ written by Ahmed Saadawi, which won the international prize for the Arabic Literature in 2014.

Ahmed Saadawi ‘s story is highly blood churning in that it narrates how a weirdly monstrous creature is made out of the collection of mutilated bodies littered in Baghdad streets during the 2005 civil war of high-degree violence and terrorism.

In our Tamil language, the translator of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein’s Monster and celebrated writer is Pudumaipithan whose horror writings in range and caliber equal those of Poe. His short fiction ‘Kanchanai’ takes the cake in aesthetic horror type.

The writings of Dino Buzzati, whose 1960 novel ‘Larger Than Life’ is still considered as the first serious novel of Italian sci-fi, have speculative nature. His novel is celebrated as the best in the Gothic literature. But, unfortunately, the succeeding horror writers have killed the life of the trend, dishing out only massive trash in the name of horror stories.

It is a literary tragedy that such cheap horror litterateurs having a global clout and lobby have produced rubbish writings and presented them before the world readers, claiming they are standard. It is thus that the Tamil’s identity steeped in third-rate commercialism is constructed in the world arena, coming as it did under the influence of the global trend.

This kind of tragedy is akin to the Shakespearean. It is a tragedy taking on the tones of that born in the seamless murders committed in power hunger.

The spirits strutting about in the ‘Vaanasuran’ performance in our folklore street-theatre are more horrible than the Macbeth witches. Vaanasuran is so-called as he is capable of changing into a ghost and flying about in the skies.

It is peculiar that the performers of ‘Vaanasuran’ would look like being possessed. In particular, the actor playing it out as Vaanasuran would invoke all kinds of evil spirits such as ‘kooli’, ‘kulli,’ goblins and imps of black magic. How majestically he would shout at the top of voice and assemble all underworld supernatural beings in his fight against Arjun, the mythological character. Something beyond the pale of human imagination!

All actors donning the robes of horror creatures would look like being in their very shoes, seemingly in the grip of some supernaturally mysterious power. The actor playing the part of Arjun, while taking on the unconquerable ‘koolis’ (demons), would swing and sway his whole body as if in a divine fervor. His ancestors’ spirits descending into his whole being, he would provoke all ghosts to vomit blood. The aesthetic experience that this phenomenon would give is unparalleled and unmatched in the world literature.

Such rituals of ancestors’ spirits slowly finding their way into their progeny are part and parcel of the aboriginal African tradition with which the Tamil has an affinity, evoking horror at its best, going by certain ancient Tamil folk ceremonies. The syndrome of being possessed is the warp and woof of the traditions in several classical languages.

Here it is worthwhile to compare one of the ancient Tamil rituals dating back to what is known as the Sangam Age – ‘velanveriyaatu’ – a divine ceremony having all ingredients of a horror stuff, with the Columbian aborigines’ renowned ritualistic dance knows as Danza de los Voladores.

This aborigines’ meaningful ritual of veneration was performed with an intention of bringing prosperity to earth and ending drought.

Researchers hold that this ritual over the years became extinct owing to the Spanish colonization and the local conversions. The dance ceremony, which held spectators under spell, had become just an event held at Catholic churches and during holidays for saints.

In 2015, in memory of world renowned Mexican painter and feminist Frida Kahlo, this dance was performed in London. By way of invoking the spirit of Frida Kahlo into the bodies of four women, the event was named as ‘The Four Fridas’ with modern connotations. The credit went to the Royal Artillery Barracks which had transformed the event into a speculative fiction, giving a post-modernist dimension to the age-old traditional ritual.

Thus, each and every clan has the horror literature in the form of ancestors’ spirits descending into the bodies of their descendants.

‘Velanveriyaatu’ refers to the ceremony, in which a love-stricken girl, mistaken by her mother for being possessed, is exorcised by a priest invoking the divine names of Lord Muruga. (Velan means the Hindu God Lord Muruga and veriyaatu a ceremony of frenzy and fervor). The Tamil Sangam literature abounds in romantic poetry having this as one of its essentials.

The Danza de los Voladores (Spanish) meaning ‘dance of the flyers’ is an age-old ceremony still in vogue in certain parts of Mexico, said to have been performed with a deep prayer to the Gods to end the prevailing drought and shower their mercies in the form of rains.

Like the Yoruba religious rituals recaptured by Nigerian Nobel award-winning writer Wole Soyinka in his writings, in my native tradition too, there is a ceremony in which the hair of ‘Saathaavu’ remaining in the stones used for foretelling and known as ‘Muthezh’ is torn out and deposited in the hollow thigh penetrated with a knife for the purpose. I assert with a note of pride that I am hailing from the antediluvian tradition. I still have in my possession the eight stones known as ‘Muthezh’ which can stand comparison with Opon Ifá, a divination tray, revived and popularized by Wole Soyinka.

In our traditional ceremonies, a folksy musical instrument called ‘udukkai’ in Tamil is used to evoke myriad feelings, mysterious and mesmeric, in the minds of the listeners; its supernatural notes beggar description. While I think of the ways in which I can give a pen portrait of the musical magic of the ‘udukkai’, in an instant flashes across my mind an article written by American woman writer Margot Singer, ‘Can a Novel Be a Fugue?, published in The Paris Review. (https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2017/07/31/can-a-novel-be-a-fugue/)

“If poetry was a kind of music, I wondered, could a novel be a fugue?” she says. I would like to quote her as follows:

"In fact, the terminology of the fugue explicitly suggests a narrative: the main theme of the fugue is called its subject, the individual parts are voices, an altered form of the subject presents an answer, and so on. Originally a form of vocal music, early fugues drew on the canzone, a type of Italian lyric poetry or song. If poetry was a kind of music, I wondered, could a novel be a fugue?"

The word ‘fugue’ is weird in that it is related to both mind and music. This can be defined as per lexicons as follows:

It is a “contrapuntal composition in which a short melody or phrase (the subject) is introduced by one part and successively taken up by others and developed by interweaving the parts.”

It also means “a loss of awareness of one's identity, often coupled with flight from one's usual environment, associated with certain forms of hysteria and epilepsy.”

Shaping up his characters in the mould of fugue having several metaphorical senses, Singer’s debut novel ‘Underground Fugue’ explores the literary possibilities of metamorphosing the narrative into a fugue.

Now, over to our indigenous ‘udukkai’!

Our horror literature is birthed by the supernaturally aesthetic mysticism of the udukkai’s musical notes, mesmeric and mysterious, which have elements of paranoid. Our ancient mystic Lord Rudra is part of our folklore, who plays this ‘udukaai,’ a musical myth of our ancient clan tradition, smearing his whole sturdy and charming physique with ashes left over in the graveyard, performing spontaneously a celestial dance amidst hordes of spirits, transforming the scenario into a magical one bristling with intoxicating notes, and evoking a feeling of horror aroused by great writings stirring the deepest feelings.

The mythical ‘udukkai’ has four kinds of talas: The first one called ‘kaaliyayi’ performed in front of the Goddess Kali temple. It is a musical form played while singing folk songs that sound like hymns to the small and big deities. The second tala is called ‘arugori’ played during singing panegyrics to ancestors, celebrating their valour and courage. The third one is branded as ‘naali’ used during sooth-saying exercise. This musical composition is a unique stream flowing in moods depending on the circumstances. But of all the talas, the most essential one is called ‘peyaachi’ or ‘evilma’ that is employed mainly in exorcism. This tala is the soul of the ‘udukkai.’ Chiefly played in the dead of midnight, the ‘evilma’ tala is highly obscurantist, changing its tone and tenor with changing ‘prahars’ of night. Set against the dark and threateningly menacing night, this tala takes on the colours of a mystery, evoking feelings of horror and fear which fill the ambience as ashes.

It is these musical notes of our Tamil folklore dating back to thousands of years ago, which set our language apart, in world music and global literature.

The question that swirled in the mind of Margot Singer takes a different form in my mind:

“Can a horror become an evilma?”

*****

Translated by : Maharathi

************************

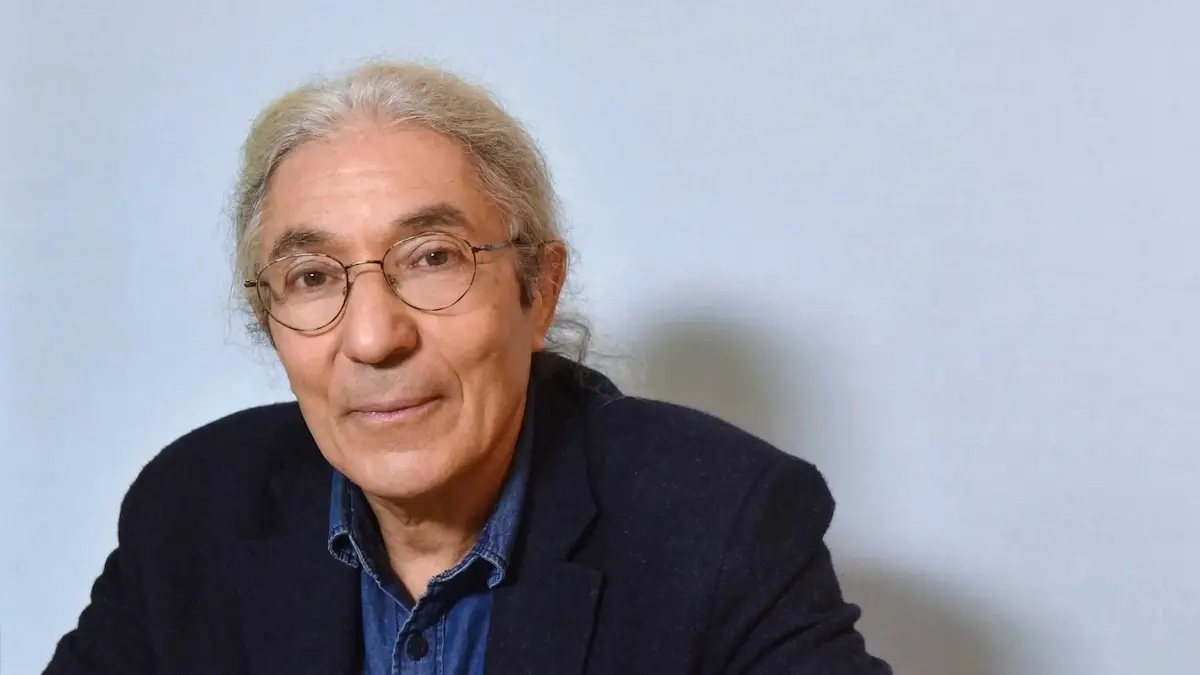

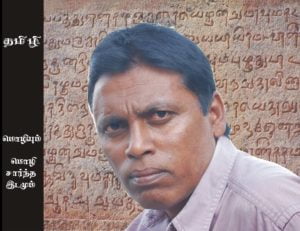

*Gouthama Siddarthan is a noted Modern Poet, short-story writer, essayist and literary critic in Tamil, who is a reputed name in the Tamil neo-literary circle.

There are 15 books so for written and published, which include series of stories and essays.

A Tamil literary magazine titled UNNATHAM is being published, under his editorship. It focuses on modern world literature.

Ten books authored by his are being published in nine world languages (Tamil, English, Spanish, German, Romanian, Bulgarian, Portuguese, Italian and Chinese) before one month..

Now, his column writing in Spanish and Italian magazines!