By Emad El-Din Aysha, PhD

I advise you to throw out altogether § 3—the “demand (women’s) for freedom of love”.

That is not really a proletarian but a bourgeois demand.

--- Vladimir Lenin, in a letter to Inessa Armand, dated 17 January 1915

For once I’m going to talk about reasonably controversial movies I did not watch too late at night. One is a respectable East German science fiction movie, Eolomea (1972). The other is a not half-bad Canadian movie of a lurid nature, Below Her Mouth (2016).

I didn’t terribly like either movie to be honest but the thematics hooked into some things I’d written about before and they even overlapped with each other in all sorts of bizarre and unexpected ways. For someone like me who is in love with follow-ups, I just couldn’t resist!

The Communist Springboard

I’ve argued repeatedly before, basing my conclusions and analysis on Marie Lathers’ work, that American science fiction and for the longest time consigned women to the backseat of human advancement, keeping them stuck on ‘mother’ earth while men were busily exploring the outer reaches of the universe, or the ‘frontier’ as Americans choose to call it. At least until the 1960s and specifically in sci-fi cinema.

This is broadly speaking true with the odd notable exception here or there, and with that gendered constructions of the nation and motherland pop up, not to mention men as protectors of the invariably helpless motherland. But is this a universal masculinist problem or a problem more endemic of the Western tradition of SF, and more specifically filmed American SF? Watching a movie like Eolomea from the German Democratic Republic helped set my priorities straight. The first scene pretty much says it all, if you’re attuned to that kind of thing.

You have an unnamed guy on an unnamed tropical resort-desert island, on the beach, yelling up to the cosmos to witness how he’s never going back into outer space again. Cut to the next scene and you have space station Margot calling Earth Central – the UN Science Council – to report vessels mysteriously disappearing without a trace, let alone a distress call.

A troublesome but brilliant scientist, Professor Oli Tal (Rolf Hoppe), pitches a hypothesis which is that antibodies have infiltrated the solar system and are destroying anything they encounter, much like antimatter colliding with matter. The scientific council doesn’t buy this thesis and decides to not risk any more space craft with a compulsory grounding of all flights for the foreseeable future, the proposal of Professor Maria Scholl (Cox Habbema), even though that means putting an end to interplanetary commerce. Maria’s chief concern of course is safeguarding lives, to Oli Tal’s chagrin.

Straight off you notice themes about humanity and the status of women in the future. You have the Science Council and it’s full of men and women and people of all races and creeds, voting democratically and discussing things reasonably. Even so you still feel that women are at a disadvantage, with Maria’s superiors (obnoxious men) complaining about her smoking and how she’s more concerned with saving lives that portioning out blame, etc.

Turns out that the person in the opening sequences, Daniel Lagny (Ivan Andonov), is actually Maria’s boyfriend and the tropical resort was the Galapagos Islands, where they first met and fell in love. He hates his job and outerspace, as brilliant as he is as a navigator, because he’s stuck on the Luna 3 asteroid with an oldtimer pilot (Vsevolod Sanayev), one of earth’s many failing outposts in the solar system. Even his co-worker, an early astronaut pioneer, is growing weary and dreams of the day he’ll meet his son on the Margot space station. Sadly his son has disappeared onboard one of those missing vessels. The boy is all the old man has in the world, having lost his family with the failure of the Venus colony. His hope more specifically is to shepherd the boy on earth and show him all the wonderful things he’s never seen or experienced, more specifically rivers and trees.

TROPIC OF PASSION: Daniel (Ivan Andonov) and Maria (Cox Habbema). There’s nothing quite like gravitational attraction to keep a man where’s he’d needed, if not wanted!

Hmmm, that’s sounds familiar doesn’t it? Mother earth, but as told from the perspective of a disenchanted man, amazingly enough. Same goes for the grumpy anti-hero Daniel who actually wants to get into trouble with the space agency and have his licence revoked so he can go back and live in all those wonderful green fields of his youth where he grew up, on his mother’s farm. All he wants is a wife and kids and a regular job. His girlfriend Maria by contrast is the one that convinces him to go back into space, when they are busy honeymooning in the Galapagos – without getting married, if you get what I mean – and she eventually gets to go into outerspace herself when they track down one of the missing vessels. (She joins the crew of the rescue vessel, against the sexist misgivings of her superiors, and goes to the Margot station to see why it’s also mysteriously fallen silent, not worried about the possibility of an outbreak). It turns out in the end that the missing ships and their crews are alive and well and that they’ve been secretly planning to head off to a planet beyond the solar system known as Eolomea, the legendary land of eternal spring. One of the scientists who discovered it was, wouldn’t you know it, the good professor Oli Tal. His daughter is one of the missing scientists-astronauts preparing to launch to this new world. Daniel, despite his grumpiness, is an adventurer at heart and his sense of obligation towards these young whippersnapper scientists heading out into the unknown forces him to join their mission. (Their original astro-navigator messed up his calculations, sending them off course). Professor Tal has been helping them all this time and he was the original dreamer that wanted to head to the stars to this possibility inhabited world; earth observatories detected a shining light coming from it that may have been a deep-space laser looking for life elsewhere. The Science Council, bunch of risk-averse bureaucrats that they were, refused to approve his proposed mission and would never approve what these kids are planning. (These guys, and gals, are as unresponsive as the UN Security Council!)

Herein lays the thematic significance as far as we’re concerned. Life on earth is portrayed in a distinct fashion, a land of decadent opulence. You notice this in the picnic scene between Maria and the good professor, and also the costume party scene where Maria and the fellow council members look like a bunch of decadent old world aristocrats. And this from an East German movie. I was surprised they could foot the bill, let alone get away with the imagery up against the censors. I had no idea the GDR were such extravagant spenders and so artistically brazen.

But, it just goes to show that while woman can represent land – Dan’s dreams of return – the desire to return to the safety and wholesomeness of mother earth is not an inherently female desire, anymore than the love of exploration and pushing the frontiers of human knowledge is somehow inherently male. The East Germans really know how to normalise this gender set-up without doing it in a cheesy politically correct fashion. Also note the antibodies thesis of Professor Tal, a classic example of othering and turning the unknown into an inherently hostile domain that never comes to fruition since it’s a phoney thesis push by the professor. (Having humanity united in SF is usually an open invitation for being united in the face of a common alien enemy, but not so here). But even he doesn’t want space journeys to be grounded, antibodies or no antibodies. (You also learn that an earth observatory once did a hoax about an unidentified flying object entering the solar system, evidence that they are bored with their lonely plight in the universe and want some extra-terrestrial company). And when he helps the rebel scientists heading to the new world, he does this as a father (for his daughter’s sake) and as a scientist fed up of bureaucracy and the easy life; exemplified by the luxurious coffee set her drinks from. It seems then that the sexism we see in much early American SF, partly movies, is more distinctly American, relying on the mythos of the frontier and the badlands not being any place for women, full of marauding Indians and bandits and gunslingers and evil rancher tycoons, not to mention morally reprehensible saloon girls and Burlesque houses. Women’s supposed hostility to open spaces is evident in smaller sci-fi flicks like Creature (1985) and also in Outland (1981), where the entire male cast have frontier-era type beards. And the frontier is explicitly mentioned in the closing scene of the SF-horror classic Alien (1979), fortunately a movie that also broke many of these gendered conventions.

Hell you can see this imagery in the horror movie Priest (2011), with vampires who used to rule the desolate lands like gods that the white man is now encroaching on. That’s not very nice, is it? Likening the original inhabitants – the natives – as a bunch of mindless, insect-like monsters ruled over by a ‘queen’. Come to think of it, didn’t we see that in Aliens (1986), a supposed chick flick by the Canadian James Cameron? Time to move onto the second movie at our disposal here, a Canadian (creature) feature of a whole other calibre!!

The White Woman’s Burden

I have to admit I was rather disappointed with Below Her Mouth, a movie I was looking forward to watching and not just for the gratuitous sex scenes. In point of fact the sex scenes are too gratuitous for their own good and also stylised, congratulatory and unrealistic, not to mention saturated with biased symbolism. There are many plus points in the movie, with snappy dialogue and cool visuals and an emotive soundtrack, but it’s a mixed bag at best. First the bad, then the good, then the sci-fi relevance. The movie, on the surface at least, tells the tale of two Lesbians who fall madly in love. There’s the protagonist (and in more than one way), the aptly named Dallas (Erika Linder), a Swedish immigrant to Canada who works at being a roofer (like a builder) and even owns her own roofing business. And there’s her sexy love interest Jasmine (Natalie Krill), the prissy prom-queen type that works in the fakery business, more commonly known as the fashion industry. I know I’m being mean here but that’s what the filmmakers are doing since Jasmine is engaged to be married and betrays her future boob of a husband – Rile (Sebastian Pigott) – who not coincidentally is the more financially successful one. The implication here is that a woman being a woman is all wrong; a woman should be a man, meaning that she should be independent and forthright and honest. Dallas brags that she doesn’t take orders from anybody, unlike Jasmine, and when she queries Jasmine about how exciting her sex-life is after all these years engaged to the same man, Jasmine replies that she knows how to keep a man interested. Cheapening herself, in other words.

CHEAPSKATES: The only thing worse that a woman (Natalie Krill) in the fashion industry, apparently, is a man (Sebastian Pigott)… married to a women ‘in’ the fashion industry!

There is a clear vilification of Jasmine, which would explain the scene where she hoodwinks a model into wearing fur, claiming that she’s anti-fur herself. You also notice how Jasmine is dressed in simple boyish clothes when she’s on the ferry ride with Dallas, whereas the rest of the time she’s showing off her accoutrements. (No comment!) The only person who gets more trashed in the movie is her poor fiancé, someone who apparently can’t excite her in bed because he’s too accommodating and considerate, whereas the brash, rude, vulgar working class guys – Dallas’s roofer employees – can get away with sexual harassment (bad mouthing Jasmine) then prove their okay guys in the end when they offer Dallas a beer when she’s feeling bad for breaking up with Jasmine. Rile’s status as the boob husband stereotype is exemplified from the word go when you first see Jasmine, at her deluxe home, with Rile sleeping his life away on her coach – not her bed or bathtub – and her putting nail polish on. She then puts some nail polish onto him, conveying a gender role-reversal, which is silly since he’s the breadwinner. When he finally decides to man up at the end and get into the bathtub with her, in imitation of Dallas, he insists on asking her permission.[1]

Dallas by contrast gropes Jasmine at a bar, without asking beforehand, which would count as date rape if a man did this, or if this was directed by the likes of Paul Verhoven. (Not to mention statuary rape, which Dallas talks about her first sexual experience, as an underaged girl, with a significantly older women). Hell, in one contrasting scene Dallas bitch slaps Jasmine. And Jasmine betrays Rile when he’s out of town, lonely and missing the ‘emotional’ attention – that’s the oldest one in the book when it comes to men betraying their wives. (Ever watch Fatal Attraction?) There is also the ‘appearance’ of Dallas and Jasmine, with one tall and blonde with a boyish haircut, and the other short and stocky and a brunette of sorts. Again that’s the oldest one in the book if you watch threesomes in porn movies. (You either get the identical twins or the colour-size-demeanour-hairstyle contrast).

Now that that’s out of the way, my perfectly valid and ‘completely’ non-vindictive criticisms, let’s get to the better and more interesting stuff. I have to admit I did like Erika Linder. She may not be as voluptuous as or as experienced an actress as Natalie Krill but she played her role quite competently and casting her was a wise choice. And that’s despite the fact that I don’t find her in the least tomboyish. She knows how to withdraw her emotions from her face and body language, leaving her looking like the female equivalent of Bill Skarsgård, the brooding, melancholy Scandinavian dude responsible for Pennywise in It (2017). Dallas’s whole problem in life is her inability to enjoy herself, punishing herself it seems for trying to be a man – outdo men at their own game – in a man’s world. You see this in the opening sequence where she is having sex with an Asiatic woman (Mayko Nguyen), not orgasming or even enjoying herself while ‘servicing’ her female lover to perfection. You can see how ‘controlled’ she is, never letting her guard down to make the mistake of falling in love, which means permanent attachments. (She brags about giving up the engagement ring when she sees Jasmine’s own ring, and she also blows off the attractive bargirl after essentially stealing her from her own roommate). Also having someone with pasty blue eyes and pale, pale white skin (not even any freckles) contrasts markedly with the Asiatic woman and this is probably deliberate on the part of the Canadian crew responsible for the film, highlighting the racial-cultural diversity Canadians are rightfully proud of and the status of Dallas as a migrant trying to integrate and reformat her identity. (Her parents fell in love with the American soap opera of the same name and decided to head off to the new world as a consequence, although they clearly got the map directions wrong!)

But you felt there was more going on here, a kind of racial antagonism, as if rednecks in Canada have become the new preyed upon minority. Her male employees are exceeding white and blond themselves. Natalie Krill also has a distinct look to her; her eyes are green but her build and skin colours and the shape of her face give her an aboriginal look. Also, in one exceptionally naughty scene Jasmine is in a bathtub (will keep the sordid details to myself) and you can’t help but notice that Dallas is sweating and splashing water from a bottle on her face to cool down, compared to the spoilt Jasmine who is at the opposite end of the career and gendered spectrum.[2] Jasmine has a contrived, la-di-da way of walking, not to mention living in a suburban house compared to the rough and tumble apartment that Dallas has struggled for so long to afford whereas Jasmine took the easy way up.[3]

To add grist to the reverse racist mill you can’t help but notice a scene at a strip club where Dallas is servicing a voluptuous blonde (more on this below) only to be chased out by a bouncer who is, by pure coincidence, black. This is my point of interest in this movie as far as the sci-fi linkup, woman as nation and Canada as a country not entirely reconciled with itself. The only difference here, compared and contrasted to American cinema, is that the woman here is not a perennial victim waiting for the frontierish hero to come and rescue her.

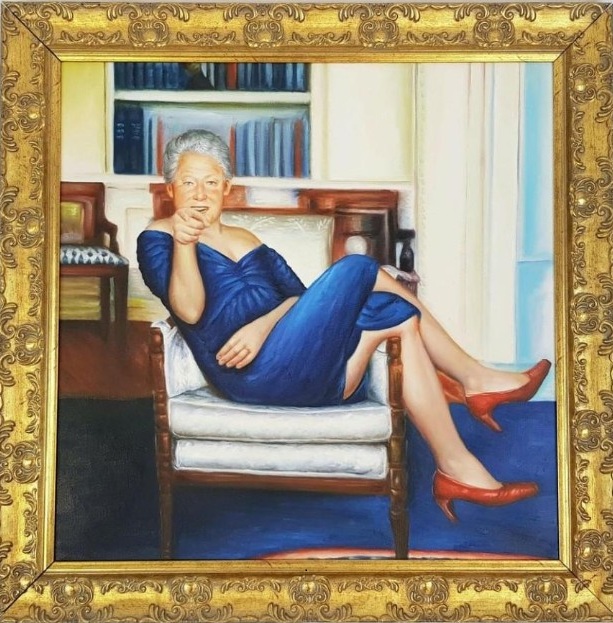

CREEPY RESEMBLANCE: Erica Linder[right] and Bill Skarsgård[left]. Nothing quite like two underaged Swedes in a pod!

Dallas fights back and builds her own career and is outspoken and forthright and the filmmakers building her up as a character doesn’t involve any excessive ‘othering’, turning opposites into all things alien, detestable and threatening. Hence, how Jasmine learns to be forthright from her and Dallas’ initial relationship with the Asiatic woman; remember what I’ve said previously about the Yellow Peril and the slit-eyed Greys? Remember also how the word alien came to supplant extra-terrestrial? Oh, and this is the same person Dallas runs to after she’s booted out of the strip club and after she’d technically broken up with Jasmine. (Her boob fiancé came back too soon from his business trip down south and found the tall, aggressive, assertive Dallas doing unspeaking ‘things’ to his hubby – special emphasis on the word thing). Not that it does the poor ex-girlfriend any good, although Dallas does apologise in the end and explain why her sense of guilt got in the way of their one-sided relationship. Jasmine, moreover, was lesbian from early on in her life but learned to forget about it, no doubt in exchange for fame and fortune. (Her fiancé is better off without her if you ask me. He should hitch up with Dallas, if he’d consider getting a sex change operation. No less there if you ask me).

The final plus point however is psychoanalytic and while I’m loath to admit it they do deal with the phenomenon of homosexuality quite seriously and with a fair amount of subtlety and depth. I’d read in a book on sexual deviance once, by Anthony Storr, that girls who over-attach to their fathers compared to their mothers are more susceptible to lesbianism and that’s precisely what happened with Dallas and even Jasmine, to a lesser extent. The mothers of both women were busybodies obsessed with appearances and running a shipshape home, whereas the fathers were more forgiving and fun to be around. Dallas’ own father is a roofer and she learned the tricks of the trade from him. (I suspect her father taught her roofing because he didn’t have any sons and wanted someone to continue the tradition).

By extension you feel, and this is a very strong plus point, that deep down Dallas hates herself; hates her appearance. (She doesn’t consider herself to be a ‘hot girl’ compared to her roommate). She services other women much as she works for clients roofing and that’s why she is the one helping the stripper enjoy herself, and not the other way around. The stripper moreover has the same complexion as her and you get the impression she’s Scandinavian too. The stripper is the woman that Dallas wants to be, and part of her fascination with Jasmine is how soft and feminine and attractive to men she is by comparison; when having sex she laughs maniacally and says you’re so pretty. (Check out poor Haley-Susanna Skaggs in season 4 of Halt and Catch Fire, and she gets attracted to a girl at a hotdog place who has tattoos and rad makeup and a tough frame, although she has – not coincidentally – the same complexion as Haley. Then Hailey gets a boyfriend at the end of the series who has the same complexion too, and the same pushover personality, which is why she pushes him around – he reminds her too much of herself).

Deviance as the New Norm

My own view on lesbianism is that it’s more generic than childhood problems, that it’s a form of mirror-imagining with women projecting their idealised selves and sense of what’s missing in them onto other, more attractive and/or assertive women. Hence, the scenes I’ve mentioned before in Henry and June (1990) and “The San Junipero” episode of Black Mirror. This movie fleshes out both theories so it is commendable for that at least. (Haley is closer to her dad too, Gordon-Scoot McNairy, a fellow geek who is always there for her compared to her mom Donna who divorced his sorry ass and screwed Cameron-Mackenzie Davis out of her company. Don’t you just love feminist role-reversals!)

That being said, I still don’t like the movie and feels it’s plagued by stereotypes. Jasmine’s betrayal of her fiancé also fits into that winner takes all motif – not a trope, a ‘motif’ – I mentioned above, evident in such annoying movies as Master of the World (1961) and When Worlds Collide (1951). For some blasted reason Americans – I mean the male variety – can’t fathom female independence and women’s lib without some form of marital betrayal, with the 1950s suburban house wife being the classic example. Ever watch Pleasantville (1998)? Seems the Canadian director (April Mullen) and writer (Stephanie Fabriz) of Below Her Mouth have fallen into that same trap, unawares I’m sure. I’m also not entirely comfortable with the psychodynamics of the Jasmine character. She talks about her first lesbian kiss as a kid on summer vacation, but the thing that specifically turns her on about Dallas is how butch and manly she is, which hardly fits in with her childhood experience of almost doing it with a spoilt brat her own age. (She’s more properly bisexual as opposed to homosexual and her dad wasn’t the strong type either). You almost feel her attraction is a classist thing, being turned on by the prospect of doing it with someone from lower down in the rungs of society, like a white girl on a plantation who befriends a poor black girl for the fun of it. Maybe I’m reading too much into this but you feel there is a little ‘othering’ in there after all, just woman-on-woman crime. Still I’m not complaining, provided they don’t pick on immigrants and Muslims and the coloured peoples of the world by invading their countries, just to make a point about themselves.

There’s a hint of othering Eolomea to be fair, since Daniel has dark haired compared to the crew of the rescue vessel – including the lovely Maria – are very blond. The actor himself is Bulgarian; his voice is dubbed throughout. (The original author of the story adapted into the movie was Bulgaria himself, the anti-fascist author Angel Wagenstein). Still, its’ benign.

Oh, and the women on display in Below Her Mouth were way too good looking as well, not that I’m complaining about that either. Same goes for Eolomea to be honest since Maria and many of her female co-workers are babes. (Turns out Cox Habbema was Dutch). Keep those Canadian and East German anti(-American)bodies flowing, if you ask me!!!

NOTES:

[1] Shades of Tom and Gordon in Halt and Catch Fire, never mind poor Laurence Olivier in Term of Trial (1962). That’s what you get for being loyal and loving and considerate and accommodating, especially in a winner-takes-all masculinist world. I hate to say this but patriarchy isn’t all it’s cracked up to be!

[2] There’s also some phallic symbolism there, making you feel that woman are having to become men in a world where men have derelicted their duties, so to speak. When Dallas breaks ups with her original girlfriend they argue and she accuses her of being hyper, much like a childish adolescent man would. (Don’t you just love it when we get vindicated, for never growing up!) Sadly it seems Freud was right about Penis Envy given the ‘things’ women use to enjoy themselves.

[3] Please don’t anybody misconstrue this as criticism of the actress herself. This is the first movie I’ve seen her in, not being familiar with Canadian cinema. From looking at her pictures online she seems to be one of the guys, equally comfortable with casual wear as the latest in fashion.