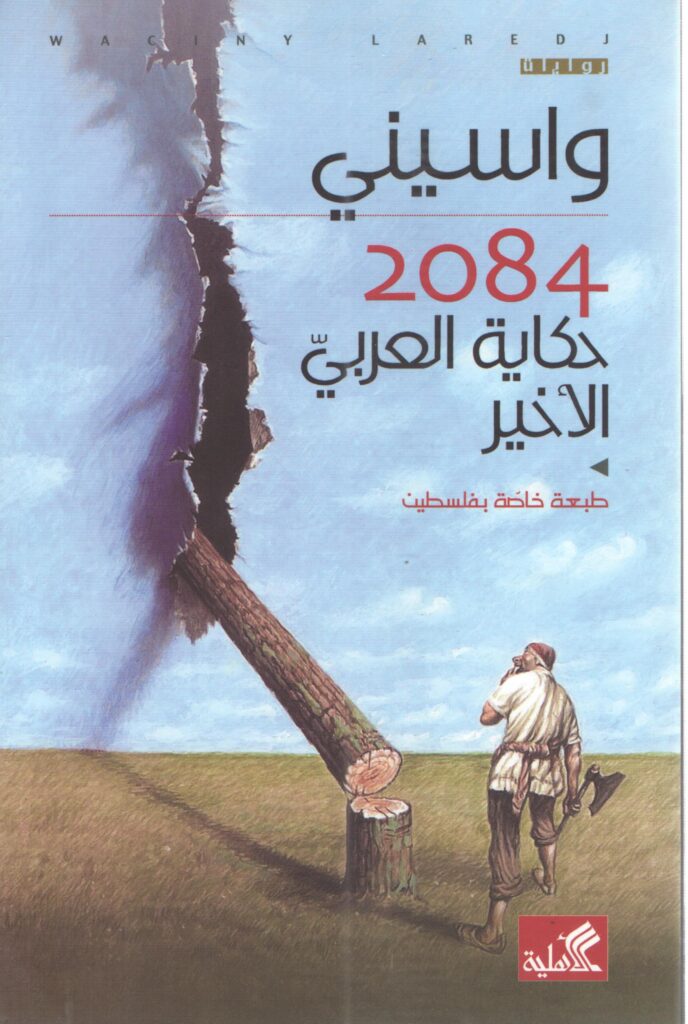

Following on from my trek through the Cairo International Book Fair, I also had the good opportunity to attend a session by Algeria’s premier author, Wasini al-Araj, who shot to international fame through his erstwhile science fiction novel 2084: The Story of the Last Arab (2015).

By Emad Aysha

Well, I hate to disappoint you, but in answer to my query, he insisted he wasn’t an SF author, as much as he loved to read from the genre, and that he never saw his novel as science fiction. To him, it was the supreme example of realism, relying on detailed analysis of the current stature of the Arabs and extrapolating from there on.

He explained that Arab commentators at the time condemned his novel for its excessive pessimism, but those commentators themselves are eating their words in the here and now, given everything that’s happened.

Wasini al-Araj predicted correctly how the Palestinian cause was going to be systematically massacred, how Syria would break up into cantons, and how the US and West would get into conflict with Russia and Iran.

FABRIC OF TIME: A cover of the aforementioned dystopian novel. It seems there's many more surprises held in store.

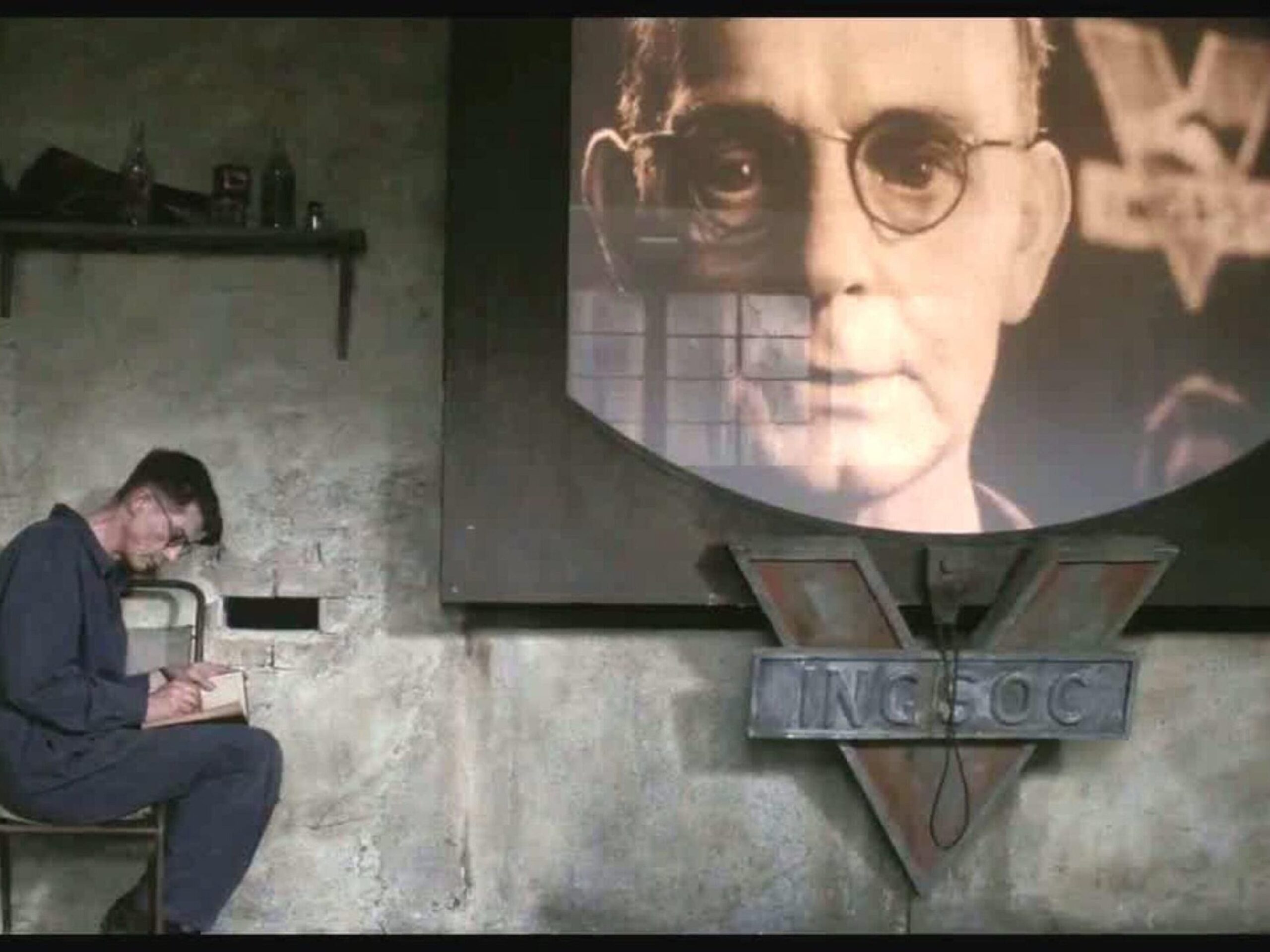

He also explained that the title of his novel was inspired in part by a pronouncement made by an Israeli Knesset member that the only good Arab was a dead Arab. Wasini added that the 84 aspect comes from Orwell’s 1984, a book that deeply influenced him while writing.

Grim, I know, but he did make a rejoinder that the new regime in Syria seems to be a united and liberal democratic one. (We’ll have to wait and see on that one.) Again, he didn’t see the novel as science fiction, advising people to read Dr Faycel Lahmeur instead, the premier expert on SF in Algeria.

Wasini al-Araj’s philosophy of writing lies elsewhere, although he does love the freedom of the imagination that comes with SF. His concerns, however, are more with reminiscences about places and people, childhood memories and first loves, and communion with the reader by reviving these self-same kinds of memories that they have.

His vehicle for all this is the expert and appropriate use of the Arabic language, something his grandmother insisted he learn, given the strict French-only education he was given in the dying days of the French occupation of Algeria.

He explained that the language you use is how you carry yourself to the reader. It has to represent you and reflect what you’re trying to get at. And wouldn’t you know it, his family’s ancestry was from Al-Andalus, one of the last families kicked out of the last Muslim enclave in Grenada.

He also lost his father during the war of independence, a trade union activist who was tortured to death by the French and whose body was thrown down a well to the point that they couldn’t identify the bones afterwards. It’s good to see how literature helps piece together the pat, a vanquished and half-erased identity, reviving it for the future.

I’ve always argued that science fiction and history are essentially the same since they study human beings along the temporal axis – the past and the future. Doing one helps you do the other, hence 2084 and Mr. Wasini’s surprisingly accurate predictions.

The same is true for Dr. Faycel al-Ahmeur’s Amin Al-Ulwani, with an author in the future reading about himself in a novel written by an author in the past and forcing himself to question himself, his career, and his self-image.

Not to mention Dr. Faycel’s novel In the Forgotten Dimension, where the protagonist journeys through a wormhole back home only to find it isn’t there anymore.

The lovely, picturesque countryside has given way to a noisy, impersonal, sterile metropolis. But there’s still the hills to take refuge in, and still the memory of the spirit to revive, with the young themselves seeking something different in the past to build a better future.

Oh, and Dr. Faycel has Andalusian blood in his veins, too. Hence, his surname Al-Ahmer, ‘the red’, from the Al-Hambra in Grenada. Time is a continuum, and the more sense of continuity you have with the past, the more you have with the future – your ‘possible’ future. Studying the past gives you a clue about the future, patterning causal chains over time.

This is the key to the emergence of science fiction, something I learned after finishing my work on Arab and Muslim Science Fiction: Critical Essays (McFarland, 2022). Identity isn’t just the past; it’s the future. Talented individuals living in nations on the rise, states in the making, try to envision what will come after independence.

PHOTO FINISH: Wasini Al-Araj [left] next to yours truly, dated 26 January after his talk. Pictured on my mobile phone.

That’s why Arab SF began in Syria and Lebanon in the 19th century, with the weakening of the Ottoman Empire and, shortly after that, Egypt. Ironically, the Turks beat them to it while the Ottoman Empire reformed and modernised.

A similar process took place in Iran, with its modernisation and literature. The same was true for Tunis in the 1920s-30s when it was approaching independence from France, and the Algerians in the 1960s when it was on the verge of kicking out the French.

That’s also why SF, in its early days, was tied up with Utopianism, trying to imagine a ‘better’ future for your country. That’s certainly true of early Arab SF, more so than the generic focus on technology that is more characteristic of Western SF.

What about the Egyptian literary scene evident at the Cairo book fair? It's a mixed bag at best. There’s quite a lot of SF, I’m glad to say, but much of it is dystopian (like Wasini’s 2084) or apocalyptic with the whole damn world or universe ending.

SF is still outweighed by horror, particularly horror with genies. I actually overheard a young man searching for books on genies, and I think he was looking for ones where humans mate with them.

Dark forces instead of casual chains over time. Time they broadcast Mr. Wasini’s talk to the whole book fair; as hypnotherapy in people’s sleep!