The United States will threaten Monday to punish individuals that cooperate with the International Criminal Court in a potential investigation of U.S. wartime actions in Afghanistan, according to people familiar with the decision.

The Trump administration is also expected to announce that it is shutting down a Palestinian diplomatic office in Washington because Palestinians have sought to use the international court to prosecute U.S. ally Israel, those people said.

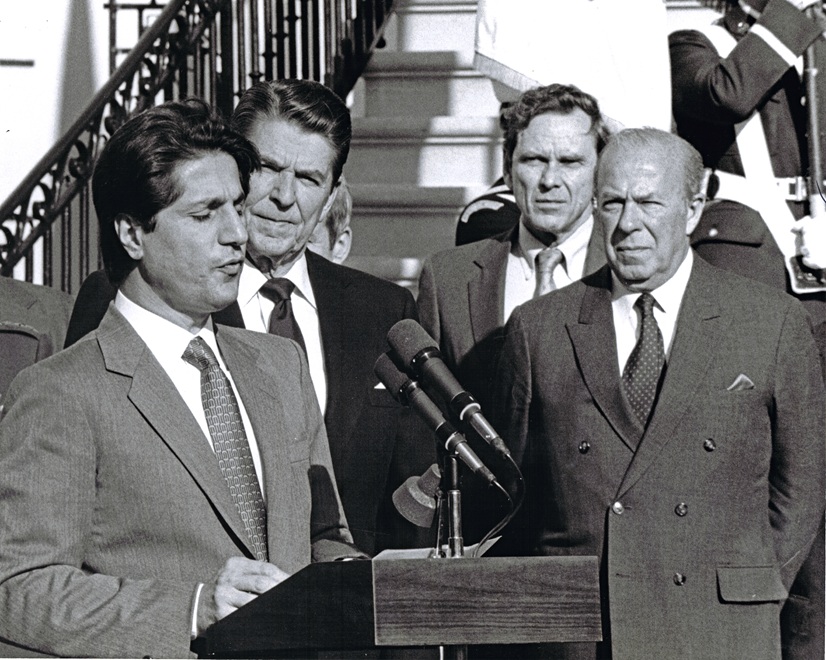

White House national security adviser John Bolton is expected to outline threats of sanctions and a ban on travel to the United States for people involved in the attempted prosecution of Americans before the international court in an address Monday.

Bolton is a longtime opponent of the court on grounds that it violates national sovereignty.

The speech, titled “Protecting American Constitutionalism and Sovereignty from International Threats,” is Bolton’s first formal address since joining the administration in April. It is sponsored by the Federalist Society, a conservative and libertarian policy group.

Bolton is expected to outline a new campaign to challenge the court’s legitimacy as it considers cases that could put the United States and close allies in jeopardy for the first time, according to individuals familiar with the planned remarks who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to do so on the record.

Bolton is likely to lay out American opposition to the court and propose measures including new agreements to shield U.S. personnel from international prosecution and the threat of sanctions or travel restrictions for people involved in prosecuting Americans.

One person said Bolton plans to use the speech to announce that the Trump administration will force the closure of the Palestine Liberation Organization’s office in Washington in a dispute over a Palestinian effort to seek prosecution of Israel through the ICC.

Bolton’s announcement is closely related to concern at the Pentagon and among intelligence agencies about potential U.S. liability to prosecution at the court over actions in Afghanistan, said a senior administration official familiar with aspects of the forthcoming announcement.

The ICC investigation of U.S. wartime actions represents exactly the kind of infringement on U.S. sovereignty that Bolton and other opponents of the court have long warned about, the official and others said.

“It’s a much more real policy matter now because of the potential liability in Afghanistan,” the official said, adding that other nations have similar concerns.

The Trump administration has questioned whether the ICC has jurisdiction to investigate and prosecute U.S. citizens for actions in Afghanistan, because Afghan, U.S. and U.S. military law all could apply in different situations, the official said.

The new broadside against the ICC follows steps by the administration challenging international cooperation in other areas. This year, the administration has withdrawn from the United Nations human rights body, halted financial support for a U.N. aid program for Palestinian refugees and threatened to pull out of the World Trade Organization.

Bolton’s speech comes two weeks before President Trump will attend the United Nations General Assembly, where he will address other world leaders. U.S. officials have said Trump will focus on U.S. claims about the threat posed by Iran and will reiterate his opposition to the international nuclear deal with Iran. Trump pulled the United States out of the deal in May.

Trump’s opposition to the Iran deal is related to a wider suspicion of international agreements and organizations such as the ICC.

Three successive U.S. administrations of both political parties have rejected the full jurisdiction of the international court over American citizens, although U.S. cooperation with the court expanded significantly under the Obama administration.

The United States has never signed the 2002 international treaty, called the Rome Treaty, that established the court, which is based in The Hague.

Stephen Pomper, who worked on issues related to the ICC in the Obama administration, said an attempt to weaken the court would exacerbate strains between the United States and allies in Europe and elsewhere who were supporters of the court.

“It’s going to create friction that’s not necessary, and it’s going to create the impression the United States is a bully and a hegemon,” said Pomper, who now is U.S. program director at the International Crisis Group.

Bolton was part of an effort during the George W. Bush administration to formalize U.S. resistance to the court, including through legislation prohibiting U.S. support and efforts to pressure other countries into agreements not to surrender U.S. citizens to the body.

Bolton’s opposition has intensified as ICC judges evaluate a request from prosecutor Fatou Bensouda, who last fall asked for permission to formally investigate alleged crimes committed during the Afghan war. That could potentially include actions by U.S. military or intelligence personnel in the detention of terrorism suspects.

Writing in the Wall Street Journal last November, Bolton said the investigation added urgency to the need to keep the United States and its citizens out of the court’s reach.

“America’s long-term security depends on refusing to recognize an iota of legitimacy” of the court, he wrote.

David Bosco, a professor at Indiana University’s School of Global and International Studies, said the judges were likely to approve Bensouda’s request.

The court is also considering a request from Palestinian authorities to probe alleged crimes committed in Palestinian territories, a step that could result in attempts to prosecute Israeli officials.

Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas, in a speech at the United Nations a year ago, called on the ICC to investigate and prosecute Israeli citizens for alleged crimes against Palestinians.

In response, the Trump administration had moved in November to close the Palestinian diplomatic office, but quickly backtracked and allowed the office to remain open with temporary restrictions.

That office serves as a de facto embassy, staffed by an ambassador, to represent Palestinian interests to the U.S. government.

The Trump administration contends that the Palestinians violated U.S. law by seeking prosecution of Israel at the ICC. The administration’s initial decision to close the office caused a breach with Abbas that widened in December when Trump announced that the United States would recognize Jerusalem as the Israeli capital and move its embassy there.

The Trump administration has not publicly committed to support a separate sovereign Palestine alongside Israel, which was the goal of previous administrations. But like previous U.S. administrations, the Trump White House considers Palestinian efforts to seek statehood recognition through international organizations to be illegitimate.

The Bush and Obama administrations sought negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians to reach that goal. The Trump administration has drafted a detailed proposal to settle the Israeli-Palestinian conflict but has not released it or publicly discussed how it would address Palestinian statehood.

Bosco said punitive moves would “mark a return to a kind of cold war between Washington and The Hague.”

But a move against the ICC is likely to generate less outcry from Congress than those against other international bodies because politicians of both parties generally oppose attempts to subject Americans, particularly service members, to international prosecution.

The ICC has been subject to international criticism for other reasons, including that it has moved slowly to convict and has focused mainly on crimes occurring in Africa.

Source: Washington Post