The 20th century was a period of political fragmentation between monarchies and republics in the Middle East. The success of monarchies was a success of British foreign policy (the Pax Britannica). Their credible history of state-building and strategically backed monarchs who unified tribal Arab society, drawing on the early European model. While republics were primed for revolution and power struggles, monarchies represented continuity and stability.

By Nadia Ahmad

The tribal/clan dynamics in Arabia resembled those of 10th-century Europe, in which monarchies provided stability within tribal societies. Even when shaped by British imperial frameworks, Jordan and the Gulf retained dynastic legitimacy, religious anchoring, tribal mediation mechanisms, and gradual institutional layering. Republics were engineered projects, while monarchies were inherited systems, with structural stability.

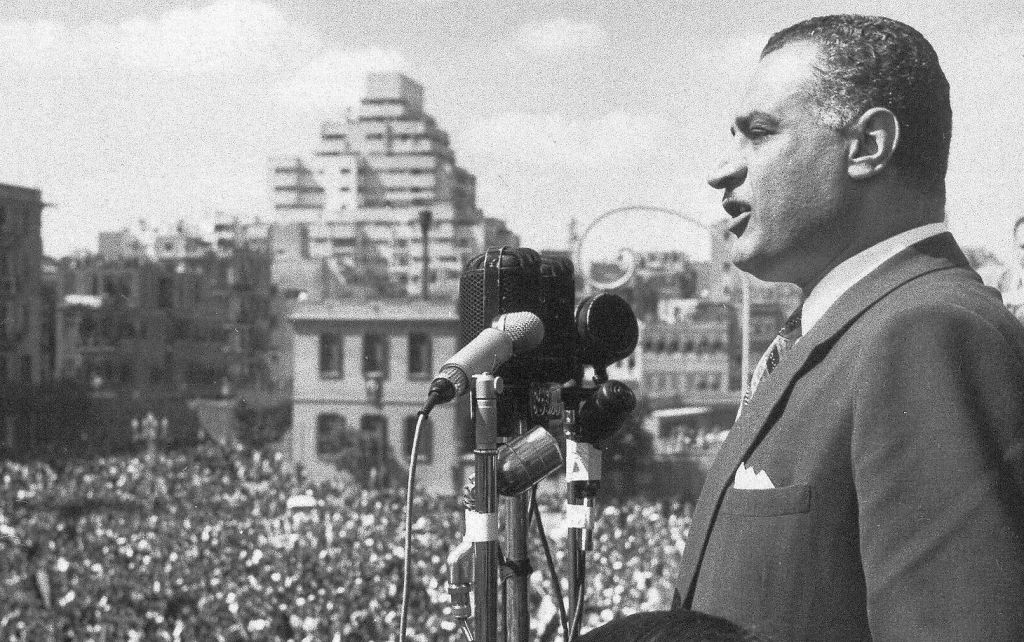

Arab republics emerged largely through military revolutions in Egypt (1952), Iraq (1958), Yemen (1969), Syria (1963), and Libya (1969). Their legitimacy was negative and reactionary; anti-colonialist, anti-monarchy, anti-Zionist, and anti-West. They defined themselves by what they rejected rather than by positive institutional tradition. By contrast, monarchies represented continuity rather than rupture.

Secularism - without liberalism – adopted by these regimes was a fatal republican illusion, used as a control tool, not a pluralist philosophy. Religion was not separate from the state but subordinate to it, producing a vacuum. No genuine religious legitimacy, no democratic legitimacy, no dynastic or historical legitimacy, resulting in a security state and rule by intelligence services rather than institutions.

Arab monarchies paradoxically survived because they were not secular; they integrated religion into legitimacy rather than suppressing it, thereby avoiding a zero-sum conflict between mosque and state. Religion became a stabiliser rather than a rival.

In governance, pan-Arabs were the equivalent of fascists and social democrats in their pursuit of Arab unification at the expense of conservative monarchies. In Europe and in the Middle East, the British rejected “oneness” and left-wing ideology.

The Failures of Pan-Arabism

Pan-Arabists adopted the proletariat-based ideology of the U.S.S.R. To pan-Arab republics, Arab monarchies and their Western allies were synonymous with “colonialism” and “imperialism”. In an attempt to delegitimise Gulf states and monarchs, they began a propaganda campaign smearing these nations as “Western proxies” and “oil reserves around which states were built”.

The Soviet choice was an economic and cognitive failure. Most Arab Republics aligned with the U.S.S.R. not only geopolitically but epistemologically: central planning, nationalisation, state monopolies, and ideological hostility to markets. This choice crippled entrepreneurship, institutional competence, and technological adaptation. After the U.S.S.R. collapsed, republican elites retained the “command mentality”, control without productivity.

Arab monarchs, particularly in the Gulf, made a different bet: Western financial systems, global markets, foreign expertise, and sovereign wealth logic. Not democratic, but economically rational.

Republics failed because pan-Arabism was rooted in Islam. Many adherents to Ba'athism were practising Muslims. Even Michel Aflaq, founder of Ba'athist thought, converted from Christianity to Islam.

In Iraq, Saddam Hussein was a Sunni pan-Arab maximalist and imperial in imagination. Saddam’s regime pursued Arab leadership fantasies, based on Islamic identity. Kurdish oppression was a consequence. Only in Syria was pan-Arabism grounded in land rather than religion.

In contrast, Gulf Arabs were contained and not politically agitating through unification fantasies. Islam, indigenous to the Gulf, was not used in the service of regional political agendas, while Levantine republics promoted unification among the Arab world, which is majority Muslim.

The conflation between language and religion among Arabs is because the Qur’an “descended” in Arabic, rendering the tongue sacred, making Arabs racist. Arab racism takes its form in anti-indigeneity, anti-Kurd (non-Arabic speakers), and an antisemitic tone.

The Syrian Paradox: The Externalisation of Collapse

The Syrian case complicates the Arab republican failure narrative, without overturning it. Syria is partially distinct, as a nation based on minoritarian power and state rationality. The Assads succeeded where other republics failed, not because Ba'athism succeeded, but Syrian Ba'athism was quietly subordinate to a second logic: minoritarian survival through state capture. The “security first” institutionalism pursued by the regime led to the architecture of a dense intelligence and military structure that functioned as a state within the state. This approach functioned for decades.

Syria did not prosper, but endured, an anomaly in the Arab Republican context. This was not a modern state in the Western sense, but a fortress state built by a minority that understood the existential risk, therefore avoided ideological excess. Syria achieved economic independence by necessity, owing to its lack of oil wealth, unlike Iraq.

Instead, the Syrian government pursued import substitution, with state-led agriculture, selective liberalisation, and regional trade creating a low-growth but resilient economy. While Iraq had oil, a larger population, and stronger historical institutions, it collapsed due to its pursuit of confrontational politics: ideological inflation that was disconnected from institutional capacity.

The Alawite faction in the Syrian Ba’athist leadership treated ideology instrumentally, not messianically, like the Sunni republican elites. Those in power understood that the state was not a vehicle for Arab unity, that ideology was not a substitute for institutions, and that survival required discipline, coherence, and control, not a romanticised revolution.

This led to a severance into pragmatic Ba'athism; slogans remained, but policy was stripped of utopian ambition. Syria pursued minimal ambition and maximal control; Iraq sought to lead the Arab world; Syria sought to outlast it. The collapse of Syria did not happen on its own. Without massive external intervention, the Syrian state would not have faced an existential risk.

The uprising of 2011 did not remain a domestic revolt; it was rapidly internationalised, above all through Turkey’s strategic decision to provide logistical support and open the borders, enabling the largest transnational flow of Jihadist fighters in the modern Middle East. The proliferation of nonstate actors, the facilitation of intelligence by the Turks, and ideological mobilisation were framed as “Sunni restoration”.

This policy was not incidental; Ankara did not merely tolerate the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood and its armed extension; it sponsored the ecosystem in which they operated. What followed was not civil war in the classical sense, but a proxy implosion fed by foreign fighters from across the Islamic world, financed through Turkey’s ally Qatar.

The Syrian regime survived 13 years, until 2024, not because it was loved, but because state cohesion proved stronger than insurgent fragmentation. The collapse of the regime did not produce sovereignty or stability but “managed chaos, " externalised violence, and permanent grey zones.

The Syrian government was aware that collapse would have meant something worse than authoritarianism, a Jihadist archipelago stretching from Aleppo to the Golan, permanently embedding a Jihadist network along Israel’s northern border. The irony is sharp: a regime long treated as an enemy turned out to be a structural stabiliser, and its erosion strengthened actors far less controllable than Damascus ever was.

The Turkish Political Islamicists

The Turks, racially and linguistically distinct from Arabs, claim to regional leadership on an Islamic basis. A revival of Ottoman influence is a policy under the government of Turkish President Erdogan. Turks have continuously used their Islamic identity for regional political influence. The Arabs' rejection of Türkiye as a leader is a cultural rejection, as Turks do not speak “sacred Arabic”.

To bridge the gap, the Turks use the Muslim Brotherhood as “something to work with”, unifying Arabs with Turks on an Islamic basis. Turkey has gone from NATO partner to neo-imperial gatekeeper.

The Muslim Brotherhood's “Arab Spring” aimed to destabilise Arab monarchies. Measures taken by the Jordanian, Saudi, and Emirati governments prevented the proliferation of this politically weaponised movement from exporting its ideology to their populations.

The “Arab Spring” affected the republics more than the monarchies because, when pressure mounted, Republics had nothing to fall back on: no dynastic loyalty, no mediating institutions, no credible reform mechanism. Their legitimacy was frozen in revolutionary slogans from the 1960s.

Monarchies absorbed the shock through patronage reform (from above), symbolic concessions, and calibrated repression. They did not promise utopia; Republics did and were judged accordingly.

Two barriers to the emergence of neo-Ottomanism are Arab monarchs and Israel.

The Tribes of Israel: Arabia and Babylon

Israel serves as a diagnostic tool for the region. The ability to normalise with Israel became a litmus test of political maturity. Republics framed Israel as an existential myth, describing it as a “state built around an army”, while monarchies framed it as a geopolitical problem.

Republics remained trapped in ideological time, while monarchies moved into historical time. This difference explains not only peace treaties but also survival itself and the real dichotomy between the two systems.

Israel is a nationalist state because it is a covenant-based on land, and has no nationalist struggle with Arab monarchies. Monarchies are reasonable politically, and not exclusionary; expansionist monarchies are imperial, not the approach of Gulf monarchs.

The harmony at the highest political level between the Arab monarchs and Israel stems from a historical bond between Arab clans and Arab Jewish tribes. Multiple Jewish tribes originated in Arabia, and since the time of the Prophet Muhammad, there have been harmonious interactions between Arab clans and Jewish tribes.

Abrahamism is not a modern policy but a deeply rooted relational dynamic between the Abrahamic tribes, Jewish and Muslim. There is no real contradiction between Muhammad and Jewish tribes, with whom Muhammad signed the first social contract in Al Madina Al Munawara (the “enlightened” city), 1000 years before Jean Jacques Russeaeu’s social contract.

In contrast, the historical relationship between Israel and the Levant has been contentious. In Babylon, modern Iraq, the Jews were persecuted, an animosity inherited intergenerationally in the collective memory of people. The Pharaonic persecution of Jews is another historical rivalry in theological historical memory.

The Tribes of Abraham

The fracture in the Arab world is not between democracy and authoritarianism, nor between secularism and religion, but between states built on rupture and ideology and states built on continuity and adaptation. Arab Republics failed because they tried to manufacture legitimacy through forced slogans and borrowed ideologies.

Arab monarchies survived because they understood a harsher truth: legitimacy is accumulated, not declared. History did not choose sides; structures did. The exclusionary policies of Arabs are absent from Gulf states, which have adopted a positive foreign policy, rejected ideological expansionism, and emphasised continuity based on structural stability.

Regarding Syria, the uncomfortable conclusion is that its collapse was not a delayed victory but a strategic error disguised as moral urgency. The assumption of strategic gain before 2024 was clear: Assad’s fall marked the collapse of an Iranian regime extension. It is now evident that the cost is not only Syrian but also regional and civilizational.

The erosion of a centralised Syrian state forces the question: Was strategic preservation sacrificed for tactical satisfaction? From a strategic preservation perspective, the Syrian state, however hostile, functioned as a border, hierarchy as deterrence logic, and a predicate adversary. Was it in the long-term interest of Israel and the West to allow the Syrian regime to fall, given what would replace state collapse?

The left-wing pan-Arabs oppose the West because they oppose Israel. They could not accept Israel because their political ideology is based on regional unification on an Arab identity, arguing that Israel took over Palestine.

Yet, it is the Muslims who have taken over the Euphrates to the Nile since 632 A.D., “liberating” Jerusalem in the process and renaming it Al Quds. Forced conversions of the Phoenicians and Assyrians Islamized the land, subsequently launching wars against Greece and Rome, turning Constantinople into Istanbul.

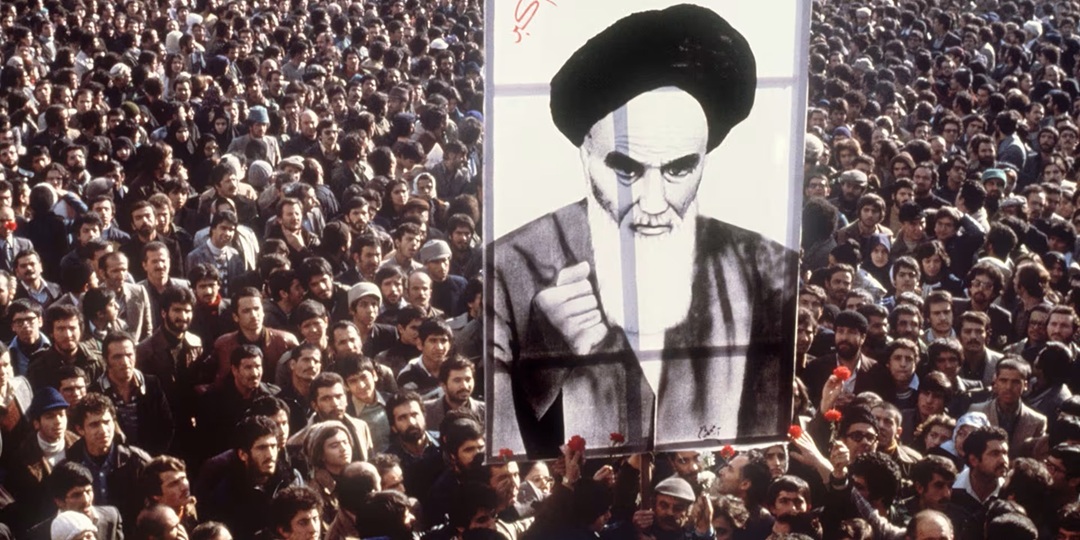

The fire of the revolutionary republics has dimmed, and monarchies continue to endure as Israel plays a growing regional role. Could this signal a step toward a more resilient balance – or do the enduring current of revolutionary politics, across the Middle East, reflected in Iran’s long-standing system and the persistence of Islamicist political movements in several countries? Whether they are in power, like Syria, or in opposition elsewhere, does that mean that peace remains a delicate possibility?