“Who Lost Turkey?”

Graham E. Fuller (grahamefuller.com)

5 August 2019

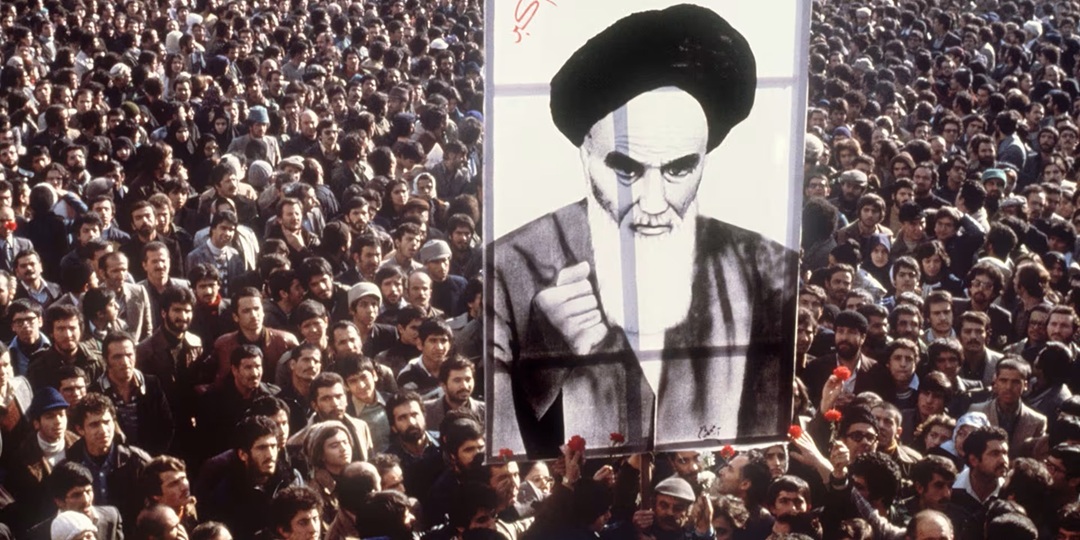

Here we go again, another phase of witch-hunting over “Who lost —-(fill in the blanks) country.” It was once who lost China in 1949, then Cuba in 1959, then Iran in 1979, and others. The latest iteration is now “Who lost Turkey?”

This question classically pops up whenever a country we thought was firmly locked into the “American camp” suddenly turns against us. Washington policy makers indeed seem to believe that, among rational nations, strategic allegiance with the US is in the natural order of things. Any defection from such an alliance is not supposed to happen, and if it ever does, “who is to blame?” How could Turkey, long a “trusted US and NATO ally,” ever develop good working ties with Russia, work in tandem with Iran, or engage with China’s new Eurasian vision?

Ankara’s actions actually make a good bit more sense if we take a broader perspective as to what Turkey has been all about over the last two or three decades.

In simplest terms, over time Turkey has increasingly struck out on its own path in full exercise of its sovereignty. During the Cold War, Turkey was deemed a “loyal” if prickly NATO ally. For Turkey the preeminent geopolitical fact was that it bordered on the Soviet Union; Russia after all had engaged in centuries of confrontation and war with the Turkish Ottoman Empire. But with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 new independent states—Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan— sprung up in this former Soviet space—right along Turkey’s eastern borders. Turkey suddenly no longer even bordered on Russia any more—a huge geopolitical shift.

At the same time, with the end of the Cold War Turks were able to start thinking of their position in the world in quite new terms. Turkey no longer saw itself as America and NATO did—as primarily a strategic eastern outpost of a Western strategic, NATO-oriented terrain. For Ankara the very meaning and purpose of NATO fell into question.

Indeed, I would argue—and in this I will be fiercely attacked by the US foreign policy establishment—that with the end of the Soviet communist empire, NATO quickly began to lose strategic relevance. (NATO of course remains fiercely defended by Washington since it has long represented the key instrument of the US foreign policy grip on Europe—often called “the Atlantic alliance.”) But with the end of communism and the fall of the Soviet Union, Europe’s identity is far less “Atlantic” than Washington would have it. Europe is now Europe, increasingly seeking greater freedom from the East-West squeeze of the US-Russian rivalry. Europe more than ever savors its own growing independence of vision, its own interpretation of its own strategic interests apart from being an instrument in the US geopolitical tool-bag. Indeed, Europe now slowly feels itself ever more part of a Eurasian space than an Atlantic one. Moscow is far closer than New York.

No doubt, Trump’s crude and insulting policy style has hastened the recrudescence of this new, more independent European identity. But it would be exceptionally short-sighted to attribute this major geopolitical trend in Europe to Trump. With the end of the Cold War, the process of greater European independence was inevitable and was already starting to evolve long before Trump. But the Washington foreign policy establishment, often in denial about geopolitical global shifts, might now well ask “who lost Europe?”

Along similar lines, Turkey too began to re-envision itself more in the historical geopolitical perspectives of the previous Turkish Ottoman Empire—an empire whose rule and influence extended politically or culturally in one way or another from Central Asian across the Middle East and into North Africa and up into the Balkans and even down into East Africa. Perhaps most importantly of all, however, the Ottoman Empire represented the very heart and seat of Sunni Islam. (This is one of the many issues over which Saudi Arabia—that cannot remotely even pretend to be a political, cultural, industrial, or even military rival to Turkey—still seethes.)

One look at political and cultural maps of the world makes it clear how much Turkey indeed is fundamentally Eurasian; its interests in Europe represent only the western wing of Turkey’s cultural wing-span, but is not even most defining wing of the Turkish geopolitical and cultural entity. Turkish foreign policy under Erdogan may have been overly ambitious in too quickly projecting itself as the dominant Sunni power in the Middle East, but arguably it is. But for Ankara the uprising in Syria in 2012 was the turning point, when Erdogan began to fumble what had been a boldly independent vision of Turkish foreign policy. [See my book “Turkey and the Arab Spring” for a deeper analysis of Turkish identity and political culture.] But Erdogan’s Syrian adventure in 2012 actually represented a major aberration from his earlier pioneering “Good Neighbor” polices and Turkey’s public embrace of it own long-suppressed Islamic identity. Bad decisions on Syria caused Turkey to lose its once firm foreign policy bearings, and it’s still not over. But Ankara is already slowly trying to recover its former foreign policy vision—as a de facto Eurasian and Islamic force.

And Ankara’s about-face in relations with Russia? Turkey is well familiar with Russia as a significant actor in the Middle East and Levant going back hundreds of years to Tsarist times. But as of 1991 Russia ceased being an expansionist empire on Turkey’s borders. And as the US worked to push NATO provocatively right up to Russia’s very doorstep, Russia increasingly shares with China the goal of stymying US failing efforts to maintain its old role of global hegemon. China itself of course has meanwhile creatively reimagined this Eurasian space with its visionary project of the One Belt One Road trans-Eurasian trade and transportation hub.

Can anyone really imagine that under these dramatic new twenty-first century realities Turkey would not involve itself heavily in this process? Indeed, does NATO mean much of anything at all any more to Turkey (or even to many European states like France or Germany) except as a useful instrument for handling its relations with the US and Europe? Nominal Turkish membership in NATO does ironically provide Turkey with a useful counterweight that lends it greater clout in its dealings with Russia and China.

In Ankara’s view then, it has little to lose, at least in terms of its own security, in severely downgrading—even if not abandoning—NATO ties through purchase of Russian S-400 air defense missile systems. As part of its dual east-west identity, it knows it would be foolish to cut all ties with the West —especially economically—just as it would be foolish to reorient itself totally to the West and turn its back on this powerful developing Eurasian project of the future.

Finally, given the US foreign policy record in the Middle East—a record of serial mistakes, miscalculations, wars and disasters, still not yet over— it would be unreal for Turkey to still wish to identify itself with such US “leadership.” Furthermore, US policy towards Iran—a neighbor of huge importance to Turkey—has been irrational ever since the devastating fall of the Shah of Iran, America’s great ally, in 1979. Iran too is proud, stubborn and nationalistic in its dealings, but Turkey knows it is destined to work with Iran on a realistic basis on key regional issues—as occasional rivals as well as sharing common interests. Despite periodic tensions,Turkey and Iran—the only two historically rooted, advanced, truly independent cultural and state powers and societies in the region—have not been at war with each other for many centuries. Ankara certainly has no desire or incentive to follow the US lead in challenging Iran in what would become a very messy affair. Even less would Ankara want to align itself with the extremist, intolerant and xenophobic form of Saudi Arabia’s Wahhabi Islam that has sought, with some worrisome success, to buy Sunni leadership for itself around the Muslim world to promote Wahhabism.

Russia is well aware of the prickly nationalist nature of Ankara’s and Tehran’s leadership in these two heavy-weight quasi-democratic states. Moscow has so far skillfully managed its relations with both states rather effectively; Washington has managed neither set of relations effectively.

After Erdogan’s brilliant decade of AKP leadership in his first decade, regrettably we have seen him lurch, starting sometime around 2013, towards a repressive and vindictive form of one-man rule; this has now made Turkey’s foreign (not to mention domestic) policies quite erratic and shaky. Yet for all the present ugliness and intolerance of the present state of the Turkish government, it still technically qualifies as a democracy, albeit a highly illiberal and repressive one. Real elections are held, and the results do matter. His skillful foreign minister over many years, Ahmet Davutoglu, who was the key intellectual and diplomatic architect of the new “Eurasian Turkey,” now seems to be reemerging on the political scene, this time as a political rival to Erdogan.

So no one in Washington has “lost” Turkey, the process has been the product of myriad new geopolitical forces. Turks furthermore find it demeaning to be regarded by Washington as a property to be “kept” or “lost,” or to accept the assumption that Ankara’s default character should be as an American “ally.” Turkey will likely be nobody’s “ally”—Russia take note. Present Turkish risk-taking with its purchase of Russian missiles and its voicing of claims to energy reserves in the Mediterranean around Cyprus reflects a risky effort by Erdogan to shift attention away from domestic problems to foreign initiatives. And Turkey will be no friend to Israel.

It would be a grievous mistake to assume that when a new Turkish leadership emerges, that it will revert to the old status of “ally” whose pliability the West had long relied upon. Any new leader at the outset may seek to mend a few fences here and there with the West, but will surely continue to pursue what Turkey sees as its expanded geopolitical destiny that includes deep engagement in Eurasia.

Graham E. Fuller is a former senior CIA official, author of numerous books on the Muslim World; his first novel is “Breaking Faith: A novel of espionage and an American’s crisis of conscience in Pakistan”; his second novel is BEAR—a novel of eco-violence in the Canadian Northwest. (Amazon, Kindle) grahamefuller.com